I wrote about finding your fit last week (be the $6 bottle of water). This week I want to tie that idea to my previous post about diminishing returns to effort when applied to a particular skill or activity.

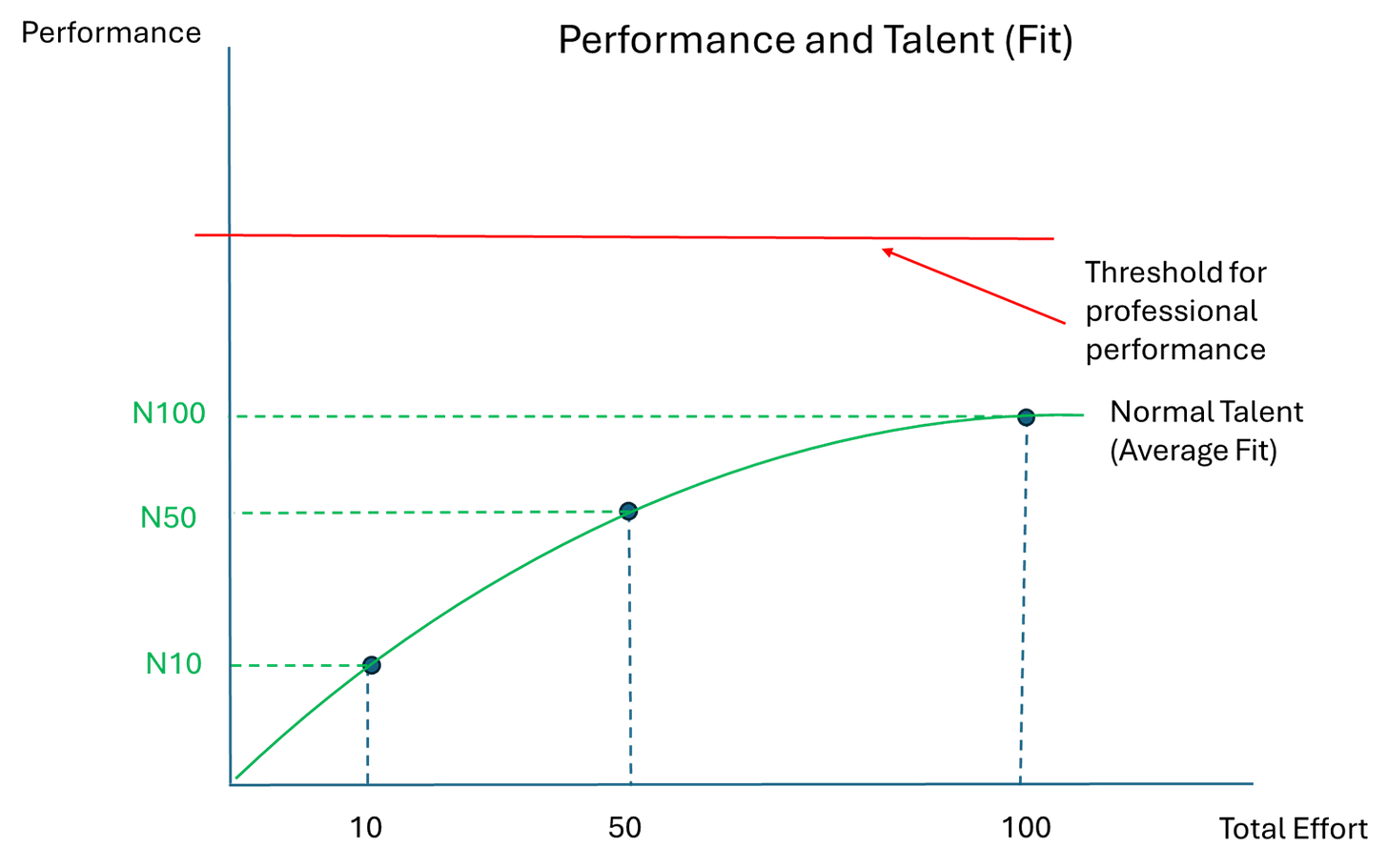

We can think of performance as a combination of raw ability, i.e., talent, and effort. We all know brilliant people who never made anything of themselves. We also all know seemingly average people who just worked harder than everyone else and turned in performance well beyond what we would have expected. In the graph above, let’s assume you have average ability for a particular task. As discussed in my previous post, Is the Juice worth the Squeeze?, most activities have diminishing returns to effort. To recap briefly, what that means is when you make your initial effort at learning a new skill, you often see rapid improvements - a high return in improved performance relative to effort. On the graph above, if you put in 10 units of effort (the numbers here are for illustration, not a precise relationship), you get an N10 level of performance. N10 is a lot better than nothing. As I often say, anything is better than nothing, especially when students don’t turn in their homework. If I put in 5X work and move to 50 units of effort, I get N50. Looking at the graph here, N50 is maybe 2X the level of performance when compared to N10. That’s nice, but it took five times the amount of effort that you had to invest to get to N10. The gain, relative to the effort required, diminishes. You really have achieved a higher level of performance, but at quite a bit of cost. If you continue to invest more effort, moving to 100 units, or 10X your original effort, you arrive at N100 level of performance, which is about 3X your level of performance when you have invested 10 units of effort. So for an additional 90 units of effort, you are about three times as good as you would have been had you just stayed with your original level of effort.

Is it worth pouring that level of effort into this project to get that level of performance? This is what I was asking when I asked rhetorically, is the juice worth the squeeze? The answer is, of course, it depends. It depends, at least in part, on how you value performance in that particular activity. You could invest a lot of effort to become a good basketball player, a good cook, or learning about medicine. Each of those areas yields performance to both raw talent and effort. You can become a passable basketball player, able to join a best-ball scramble for an afternoon, with relatively little effort. You can learn to make passable meals for yourself and your family with relatively little effort. You can learn a little first aid and self-care with relatively little effort. But to become a doctor, you have to invest a lot of effort, even if you are talented. To become a professional basketball player requires both talent and a lot of hard work. To become a professional cook probably requires the least amount of raw talent and effort - if you are going to be a line cook at a burger joint. To become a chef at a Michelin Starred restaurant requires a whole other level of both talent and effort, akin to being a professional basketball player, and perhaps harder than being a doctor. But then again, it depends.

So is the juice worth the squeeze? Let’s see if we can answer that. I can do some first aid at home, but you wouldn’t pay me to be your doctor. My medical performance level is somewhere down at the bottom - like N2. Doctors aren’t all equal. The idea behind professional licensing is to draw a hard line at the minimum required level of ability for someone to sell their services as a professional. Let’s assume that the threshold for professional performance in medicine is N80, where the red line is drawn on the graph above. If that performance curve represents me, I would have to put in something close to 100 units of effort to achieve the level of performance that would allow me to practice as a doctor. If I put in 50, I would not hit the threshold to pass licensure. We can re-imagine that answer for the other two examples - being a chef or pro ball player. The difference with the chef and basketball player is that there isn’t a licensing regime. Instead, you have to compete with all the other people who would like to be a Michelin chef or pro basketball player.

It’s possible, given my talent, that the threshold to be a professional in a particular area is above any level of performance I can achieve, regardless of how much work I put in. That would look like this:

In this example, let’s say the professional threshold is N130. Even if I put 100 units of effort in, I am not going to be able to perform at a level where I could be a professional, and given the diminishing nature of the performance curve, even if I went to 200 units, I probably wouldn’t get there. I just don’t have the talent to do this work at a professional level, no matter how hard I try. I’m 5’8”. I know there are examples of pro basketball players who are under six feet, but they are few and far between, and they have other unique combinations of skills and abilities that I was not born with. The performance threshold for becoming a professional basketball player is above my performance curve for any level of effort. I could invest all of my effort in chasing the dream of being a pro ball player and the dream never would have come true. Being a professional basketball player is not a good fit for me. I would be wasting my time if I continued to pursue my dream of being a professional basketball player after it became clear that I lacked the ability, regardless of the amount of effort.

What if I have a high level of talent (i.e., high level of fit) for a particular activity? We all have friends for whom particular skills just come naturally. Undoubtedly, you had that one athletic friend who could play any sport, or for whom at least one sport just came naturally to them, while you struggled to keep up. Your friend would be demonstrating high talent, as depicted below.

If you each put in 10 units of effort, you would perform at N10 and your friend at H10. After the same amount of practice, your friend would dribble the ball around you and leave you standing there. You would only be slightly better than your friend if they put in only 10 units of effort and you put in 50. But at 50 units for both of you, it would be like the two of you were playing different game, and it only gets worse at 100.

Your friend has to work hard - something more than 50 units of effort - let’s say 70 - but if they do, they have the ability to do this activity as a profession - they can play ball in the NBA, lead a Michelin starred restaurant, or be a doctor. They are a good fit for this activity, whatever it is. It still requires effort - and quite a bit of effort - but they can get there, while you cannot.

The beautiful thing about this is that, while there are a lot of things where I cannot achieve a high enough level of performance to be a professional, there are many where I could.

You and I, and everyone else, have a mix of talents, and therefore a mix of potential performance curves. There’s something each of us has a high talent for, which allows us to achieve high performance with ease, and the rest are normal/average, or maybe just poor. In addition to being short, I have no rhythm. Not only could I never have been a pro basketball player, I was never going to be a professional dancer or musician. Like, I don’t even have normal talent in that area. I have below-average talent. And that’s totally fine. TLW only has to put up with my dancing when I am cooking in the kitchen. It’s never going to pay the bills, and never was. Luckily, I’ve demonstrated talent in a few areas that take me over the minimum threshold for professional performance, and I can comfortably make a living.

You can be the $6 bottle of water if you find the right activities to pursue. When I write about my meaning heuristic

Meaning = Competence x Contribution x Connection

This idea of finding the right activity where you fit ties into both competence and contribution. If you find the right fit, you can achieve high levels of competence with relative ease. And if you can perform at a high level, you can contribute more. I think intuiting these curves helps you increase your experience of a meaningful and worthy life. Part of my conception of generalized competence is being able to support yourself financially - being able to take responsibility for yourself, and for anyone else whom you have agreed to be responsible for. Achieving a level of competence in something that allows you to achieve professional performance, and thus financial independence, is vital for living a worthy life.

More to say on this topic, as we haven’t completely addressed the question of which activities we should engage in, beyond the duty to support oneself and those one is responsible for. There is, of course, plenty worth doing in life that is not directed toward financial independence. More on that in another post as this one is already too long.