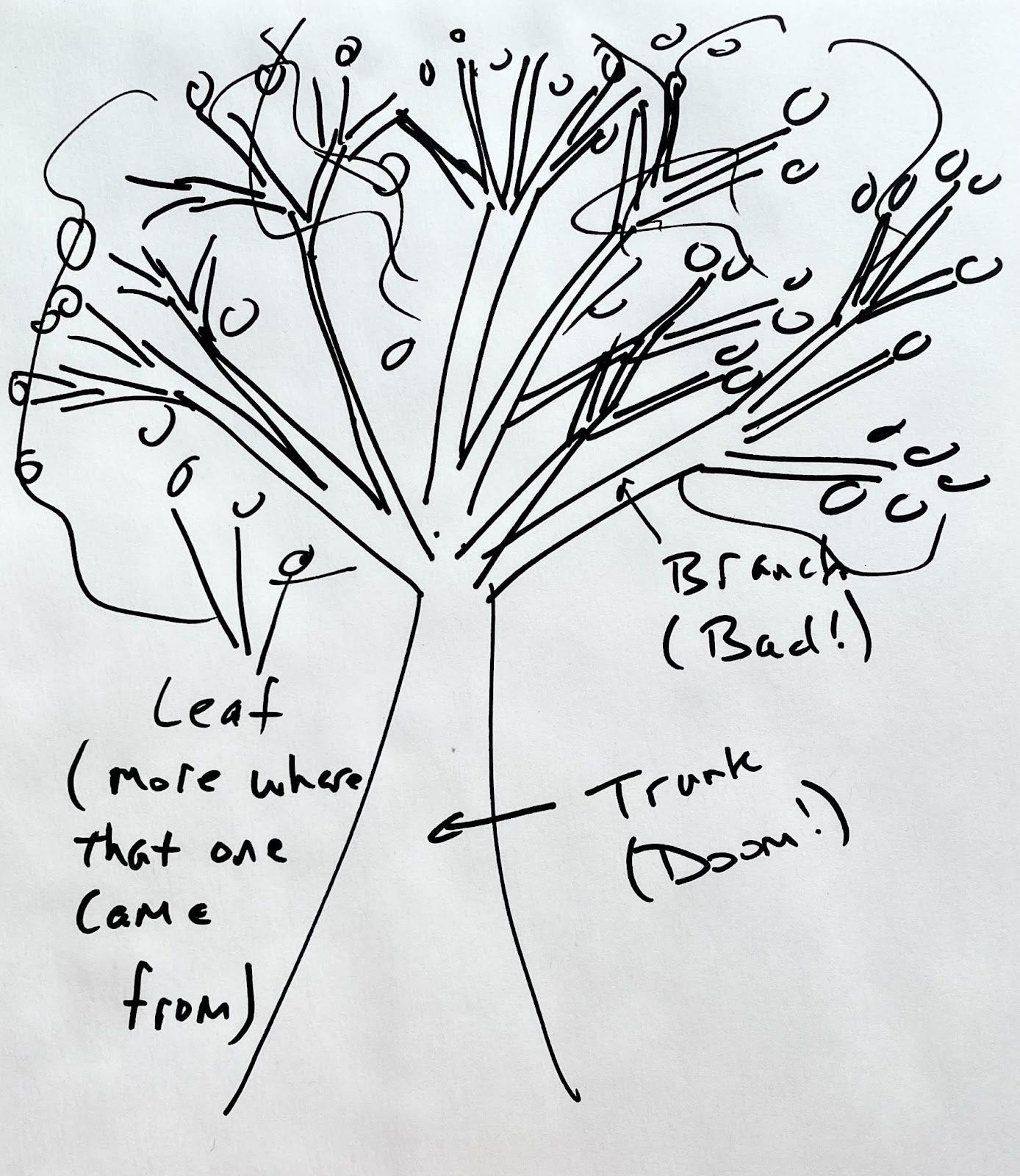

A colleague once described a model of risk as a tree. The basic model has three levels of risk:

Trunk risk = Doom! - i.e., existential risk. If you cut down the trunk of a tree, game over.

Branch risk = Bad! - i.e., costly but survivable. A tree has lots of branches. It can lose a few without too much long-term harm.

Leaf risk = More where that came from - i.e., no real cost. There are so many leaves on a typical tree that it can afford to lose many of them without even really noticing.

I think this model provides a useful analytical system for thinking about different kinds of risk. Everything we do involves some level of risk, from the moment we roll out of bed in the morning, to the moment we lay back down to go to sleep. Accurately evaluating risk and then taking steps to manage it are critical for living a successful and flourishing life. In order to accomplish anything, we have to take some level of risk, thus on a day-to-day basis, we are making risk-return estimates.

I work with a lot of emerging adults. The major tasks of emerging adulthood include launching a career, achieving financial independence from their parents, and hopefully finding a life-partner to establish a household with. Let’s analyze the last one - finding a life-partner - with the tree model.

Dating → Leaf risk. No long-term commitment, you might get your heart broken, but that’s the way it goes. There’s always someone else to swipe right on once you get back on your feet.

Living together → Branch risk. Both names on the lease means shared financial obligations. Shared things - who owns what - becomes more vague. Splitting up is doable without major long-term repercussions, but there’s going to be pain beyond just a broken heart.

Marriage and children → Trunk risk. Marriage is a legal status, as is being divorced. Add children to the mix and you have permanent costs with large externalities (the costs on the children) of splitting up. Divorce is not really Doom! as in death, in today’s world, but it does come at a very high cost, even if it is justified. Children are irreversible. There’s no re-do.

The tree model suggests date all you want - it’s low risk and has the potential for high return. You only get to marriage and children, one of the important goals of a flourishing life, by dating. It’s a good way to learn what you want and what you do not want. The tree model suggests moving from dating to living together should be weighed carefully. It’s the next logical step toward the goal of marriage. Living together is very different from dating. You find out what the person is like at their worst, not just at their best. It provides valuable information to determine if you are compatible for the long-term challenges of marriage and children that you cannot get from simply dating. The model suggests marriage (and children) is a trunk risk. A marriage can be dissolved, but that process is very costly. It makes you vulnerable to exploitation by a bad spouse, of course, which is why divorce should be possible, but it also makes you responsible for everything that happens to both of you, whether it is your fault or not. That’s the whole, “for better or for worse”. When you get married, you agree to accept the someone else’s life risk as well as your own life risk. Having kids isn’t a contract - it is an ultimate responsibility. There is no undoing a kid - it is an irreversible decision. You can be a bad parent, not taking responsibility for your kid, but you can’t undo being a parent. Marriage and children create massive risks that are only partially under your control. That’s why I think of them as trunk risks. That isn’t to say that the risks aren’t worth it, but they are real and profound risks.

This model applies well in the workplace. Trunk risks are gambles that could make a firm go bankrupt. They are “bet the farm” risks and should not be undertaken except in dire circumstances. Branch risks are the kind of risks that need to be carefully considered before being undertaken. The reward must be worth the potential loss. Deliberate, high-level review should be used. Leaf risks have such minimal consequences that they can largely be undertaken without review. Employees should be allowed to undertake these risks and use their good sense. Learning organizations encourage their workforces to experiment with low-risk innovations. It’s possible that a low-risk innovation might turn up a new idea, approach, or product.

Nassim Taleb’s book Antrifragile emphasizes the benefit of engaging in leaf-like risks that have the potential to result in massive wins. Imagine playing a nickel slot machine in Vegas that has a potential jackpot of $100,000. Assuming you get a kick out of playing the slots, you could sit for hours playing nickels and even if you don’t win, you wouldn’t be out much. Let’s say you play 1,000 nickels - that would only be $50. That’s less than what you are likely to spend on dinner when you get up and go to the buffet. Definitely leaf risk-level.

What Taleb emphasizes is looking for favorable asymmetries, where the expected payoff is greater than the cost. This means that if there was a 50% chance of winning the $100,000 if you bet your nickel, the expected value of the payout would be $50,000 (.5 x $100,000), and would only cost you $0.05. If it was 1/100, the expected payout would be $1,000 (.01 x $100,000), still far more than the cost of playing. These are all examples of asymmetric payouts in your favor. A symmetric payout would be if the probability of winning was 1 in 2,000,000, which would result in an expected payout of $.05 and a cost of $0.05. This is called a “fair game”. So as long as the chance of winning is better than 1 in 2,000,000, you may as well play - assuming the cost of playing is trivial. In reality, most games of chance in casinos are asymmetric in favor of the casino - that is to say that the expected payout is less than the cost of playing. In a real casino, our slot machine would have a 1 in 2,000,001 chance of winning, resulting in an expected payout that is less than the cost of playing. The only reason you should play in that situation is because you enjoy playing. If you play long enough, you are guaranteed to lose money. So gambling is an entertainment - you expect to pay just like you would if you went to the movies or a concert.

The above logic assumes leaf risk. Assume instead you had to bet $100,000 each time you wanted to take a spin at the slot machine. Assume also that the payout is now $1,000,000 - a 10X payout. This is a fair game - 10% x $1,000,000 = $100,000 - the expected payout is the same as the cost of playing. The problem is, unless you are very wealthy, $100,000 is not a leaf gamble. It is somewhere between branch (serious financial harm) and trunk (financial ruin). So even if the gamble has favorable odds, it can still be a branch or trunk risk, and should be treated carefully, if not avoided completely.

In addition to avoiding trunk risks and minimizing branch risks, one of the keys to flourishing is to find asymmetric payouts in life that are stacked in your favor (these are the little gambles like the one above where a nickel bet can potentially get you $100,000). Leaf risk-level activities can help you identify these beneficial risks. One of the best, leaf-level risks is meeting people and getting to know them. I can’t think of any other low-risk way to increase the possibility of finding high payout opportunities. It’s why I push my students to go to conferences and meetings and talk to our alumni. When people get to know you, as long as you aren’t a complete jerk, they typically want to help you. They will not only pass along information about work opportunities, they will tell you about all sorts of things that you might want to know - often things that have high value for you at low cost - i.e., opportunities for asymmetric payouts. These might be social opportunities, events you haven’t heard of, great places to go kayaking, or jobs. Have you ever noticed some people seem incredibly lucky? It’s probably because they have great networks and they are willing to take leaf risks.

I think of myself as a fundamentally risk-averse person, meaning I don’t like risk. I have never been a danger junky. But I think I do take a lot of risks - they just tend to be leaf risks, rather than branch and trunk risks. When they go wrong, the cost is minimal. When riding a motorcycle at 120 MPH on a winding road goes wrong, there’s usually not much to be done about it. Being able to tell the difference between leaf, branch, and trunk matters a lot. Sometimes what looks like a leaf turns out to be something much more risky. Being able to see downstream comes with age and wisdom and, of course, making mistakes.

Losing a leaf or two or a hundred leaves you in the game. Losing a few branches leaves you in the game. Losing the trunk is game over. To win, the most important thing is to be able to keep playing.