In a pivotal scene in the 1993 movie Groundhog Day, Bill Murray’s character asks, “What would you do if you were stuck in one place, and every day was exactly the same, and nothing that you did mattered?”

Here’s the clip:

The following has spoilers, but you have had 32 years, so if you haven’t seen it yet, stop reading now and go watch it.

I heard this clip played this week and it got me thinking about the movie. I am going to assume you have seen it, but I’ll refresh a little. Murray’s character, Phil Connors, a cynical weather man, is sent to Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, to cover the very cheesy annual Groundhog Day festivities. He wakes up in the morning and realizes he is trapped in a time loop, reliving the same day over and over. Initially he seeks to use his knowledge of the day for his own gain but eventually despairs. This is when the above scene happens. It is only when he learns to use his time to better himself and others that he is finally released from the time loop.

I recently discovered an Instagram account, pastvision.ai, where the owner is producing AI videos of elderly or deceased celebrities going backward in time through their various roles and life events while playing the 1984 Alphaville classic, “Forever Young”. Here’s one of the actress Betty White:

Maybe I like the videos because the song is firmly in my coming-of-age soundtrack (parachute pants, members only jackets, and all), but I’ve watched a bunch of these and there is something very cool about the backward flow of time. I was talking to my friend and colleague TB last week and we were both laughing about how the trajectory of our careers would have made no sense if one started at the beginning and moved forward, but looking backward, the things we have done and how we have come to them make some sense. So watching these retrospectives of celebrities (I am not normally a person who cares much about celebrities – TLW almost always has to tell me their names and where I have seen them before) feels like it reinforces that retrospective nature of life. As the poet Wordsworth once wrote, “The Child is father of the Man”. We can look backward to the child and see, as if it were inevitable, the man he becomes, but looking at the child alone, it’s hard to know anything. At some point, these actors/actresses change. They lose their youth. Some of them become richer, deeper, more powerful because they connect to something else. But first they had to be young.

Groundhog Day captures mid-life’s pivot. Murray, the actor, was about 42 when he was filming the movie. Right at the end of youth and the beginning of mid-life. I’ve read and written about a number of books that give an accounting of this pivot. Here’s some I recommend:

Midlife: A Philosophical Guide by Kieran Setiya

From Strength to Strength: Finding Success, Happiness, and Deep Purpose in the Second Half of Life by Arthur Brooks

The Second Mountain by David Brooks

Falling Upward, Revised and Updated: A Spirituality for the Two Halves of Life by Richard Rohr

Something changes at midlife. Things don’t make sense the way they did. Before all of these, the psychologist Carl Jung wrote:

One cannot live the afternoon of life according to the program of life’s morning; for what was great in the morning will be of little importance in the evening, and what in the morning was true will at evening become a lie.[1]

Rohr writes of Jung’s observation:

It was Carl Jung who first popularized the phrase “the two halves of life” to describe the two major tangents and tasks of any human life. The first half of life is spent building our sense of identity, importance, and security—what I would call the false self and Freud might call the ego self. Jung emphasizes the importance and value of a healthy ego structure. But inevitably you discover, often through failure or a significant loss, that your conscious self is not all of you, but only the acceptable you. You will find your real purpose and identity at a much deeper level than the positive image you present to the world.

In the second half of life, the ego still has a place, but now in the service of the True Self or soul, your inner and inherent identity. Your ego is the container that holds you all together, so now its strength is an advantage… In the second half of life we discover that it is no longer sufficient to find meaning in being successful or healthy. We need a deeper source of purpose. According to Jung, “Meaning makes a great many things endurable—perhaps everything.

The first part of life is getting good at doing things. It’s about learning a skill that will earn you a place in the world, it’s about earning your independence, it’s about proving that you are a worthy member of society. The symbols of the first part of life are material. It is by definition and function self-centered. One is discovering one’s self. The second part of life is about generativity – it is about helping others through the first part of life. It is about finding connection not only with other people, but with (and this is a bit woo-woo) the spiritual. I don’t think you are really ready to make the jump to Part 2 until you have reached midlife. You have to have accumulated a certain amount of wisdom before you are ready, and you need to find your contributions in Part 1 first as well.

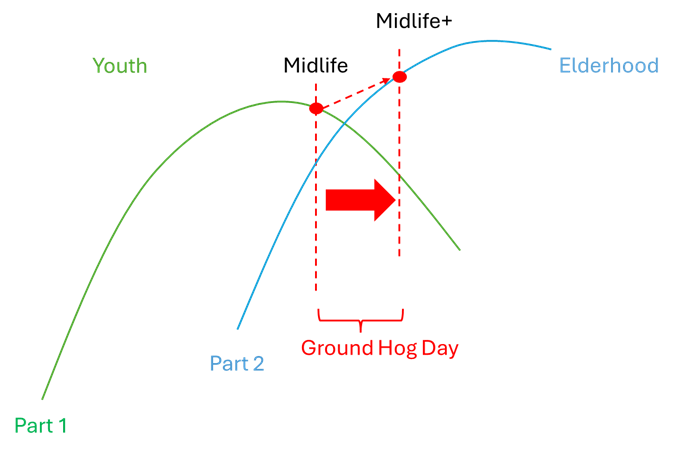

This is the lesson of each of these other books. D. Brooks uses the metaphor of the second mountain. I visualize it like this:

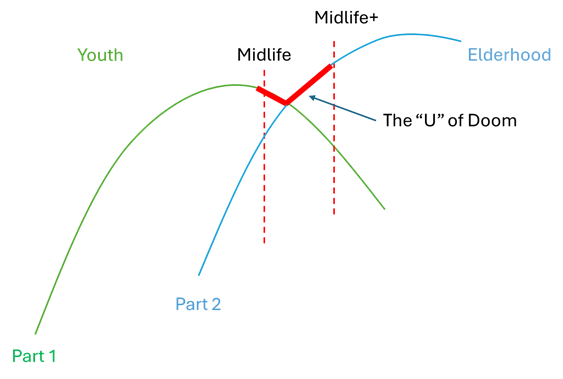

Statistically speaking, the least happy point in life, especially for men, is midlife. I think that is because the rewards of the first part of life have peaked and are beginning to decline, while the rewards of the second half of life have not yet become clear. (I wrote about this in the U of Doom). If one could literally see the points on the curves, one would see decline on the path one had been on, and something lower and possibly rising (Part 2), but who knows, other than it is less joyful than what I once had. This is the midlife crisis. It’s hard to see the possibility of the Life – Part 2 line at midlife. There is an overwhelming sense of decline and net loss. I think this is the moment Groundhog Day captures. If you can jump from the Part 1 line and let it go, and get on the Part 2 line, there is the possibility of continued growth.

In the story of Groundhog Day, Murray/Connors makes the leap from the Part 1 line to the Part 2 line. We don’t really see him enacting his Part 1 line successfully – in fact, it’s clear he’s peaked and is well into decline along the Part 1 line. We know this because of his deep dissatisfaction and the cynicism he displays about his work and his treatment of others. But by the end of the movie, he has successfully made the leap and his happiness is restored – he is arcing upward once again.

The alternative story is the person who tries to hang on to Part 1 rewards of life. I think Hollywood is a great example here. How many elderly stars look like stretched, scary, plastic models of what they once looked like in youth? Women who continue to dress like they did when they were young, men who chase young women to prove they are still young (and not just creepy)?

The “U of Doom” (perhaps the “V” or “check mark” of Doom – it just doesn’t sound as ominous) happens somewhere between the time we sense our youth fading and we successfully make the leap to Part 2. Too many people get trapped there, or act out because they do not see a way forward (the cause of the midlife crisis).

In the movie, Murray turns to a couple of drunks at a bar and asks the question I started this post with, “What would you do if you were stuck in one place, and every day was exactly the same, and nothing that you did mattered?” The response he gets from Drunk 1 is, “That about sums it up for me.” That’s someone who hasn’t found his way onto Part 2, perhaps not even Part 1.

We should begin with the end in mind: we will die and be forgotten. That reality urges us to use the time we have meaningfully, to move from the self-centered pursuits of youth to the more generative, connective, and meaningful pursuits of midlife and beyond. As Groundhog Day illustrates, it’s only when Phil Connors lets go of his self-serving goals and turns his attention toward bettering himself and helping others that he finds purpose and freedom. So too with us: true meaning comes not from clinging to fading youth, but from growing into a deeper, more generous life that benefits others and brings genuine fulfillment.

[1] C. G. Jung, The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche (Routledge and Kegan Paul: 1960), 399.