The Lieutenant-Mobile and Other Bad Ideas

Categorizing financial decisions for better outcomes

When I first went on active duty back in the early 90’s, one of the units I served with was the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment (ACR). Specifically, I was in one of the cavalry squadrons, 3/3, Thunder Squadron. Line units like Thunder Squadron are mostly populated with young people because it is a very hierarchical unit. Most of the officers were newly minted lieutenants out of West Point because assignment to the ACR at the time was regarded as a high-status assignment for a new Armor officer (I am neither a West Point grad, nor was I an Armor officer). Young people who suddenly have freedom and money (especially coming out of four years at West Point) tend to indulge their freedom, but they don’t always make great choices with this new found freedom. I have some stories about that, but the one I want to share is what I consider to be a general categorical error, the lieutenant-mobile.

[1994 Mustang Convertable, pic by Sicnag, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons]

I have a distinct memory of going to one of our social events for all of the Squadron officers, pulling into the parking lot and looking around and seeing the lot practically full of convertible Ford Mustangs. These were the cars of choice of young lieutenants. One of the things about young people everywhere is they don’t tend to think for themselves. I walk around campus in the late fall here and there is a uniform for most of the young women - Ugg boots, black tights, and a NorthFace fleece. So the Ford Mustang was the go-to car for these kids. Which car is the preferred car has probably changed, but I suspect if I were to go to the Thunder Squadron parking lot today, it would be full of some sort of sports car, and most of them would be the same make and model. What was I pulling into the parking lot in? You might have guessed by now that it was not a Ford Mustang. No, it was a sensible Honda Civic.

There was nothing wrong, really, with these guys (they were all guys - women were not allowed in the combat arms at the time) buying Mustangs. They mostly had no college debt (West Point is free), and they were making decent money for new grads. Plus if you are in the dating market, do you really want to pick up your date in a sensible Honda Civic? I guess it depends on the kind of person you want to date.

To me, the main difference is in the cost. At the time, the Mustang of choice in Thunder Squadron cost about $24,640, twice, maybe a little more, than a sensible Civic. A new lieutenant had an annual salary of about $26,600 in 1994. This meant that they were buying cars equal to almost a year’s earnings. Although they didn’t likely have college debt, they didn’t have savings, either, which meant taking out loans to buy their cars, which meant they were incurring monthly payments. I didn’t have savings either, so I had a monthly payment, too, but mine was half what theirs were. Plus insurance on a sensible Civic is quite a bit less than insurance on a muscle car, especially when the muscle car is being driven by a young man. This left me with more flexibility with my income than they had. More flexibility translates into more freedom. And for me, at least, freedom is the most important goal. As I quoted Thoreau last week, and I will repeat it again: “[A] man is rich in proportion to the number of things which he can afford to let alone.”

Buying a car with debt creates a fixed, mandatory expenditure each month: you have to make your car payments. If you do not make them, some unpleasant guy with a big wrench shows up in a tow truck and hauls your car off. Having a car is a choice. There are other options - walk, bike, public transport, etc. Some of those options depend on your choice of housing, of course. But even if you need a car, how much you spend on a car is a choice. Buying a Mustang creates a larger, fixed, mandatory expenditure than buying a Civic. Both will get you from point A to point B. But one of them reduces your financial freedom more than the other.

I started talking about personal financial management with my seniors a couple of years ago. I do talk about things like retirement accounts and insurance, but I really believe the most essential element of financial success is understanding the difference between mandatory and optional expenditures, and fixed and variable expenditures.

Mandatory: Things you don’t have a choice about buying - like food and shelter.

Optional: Things you can do without, but might add joy to your life - like going to a movie.

Fixed: Once you commit, you have a stream of payments you will have to make going into the future for some period of time. These decisions constrain your financial freedom in the future. Anything bought with debt is a fixed expense.

Variable: You can control how large the expenditure is. There is no commitment to a specific expenditure.

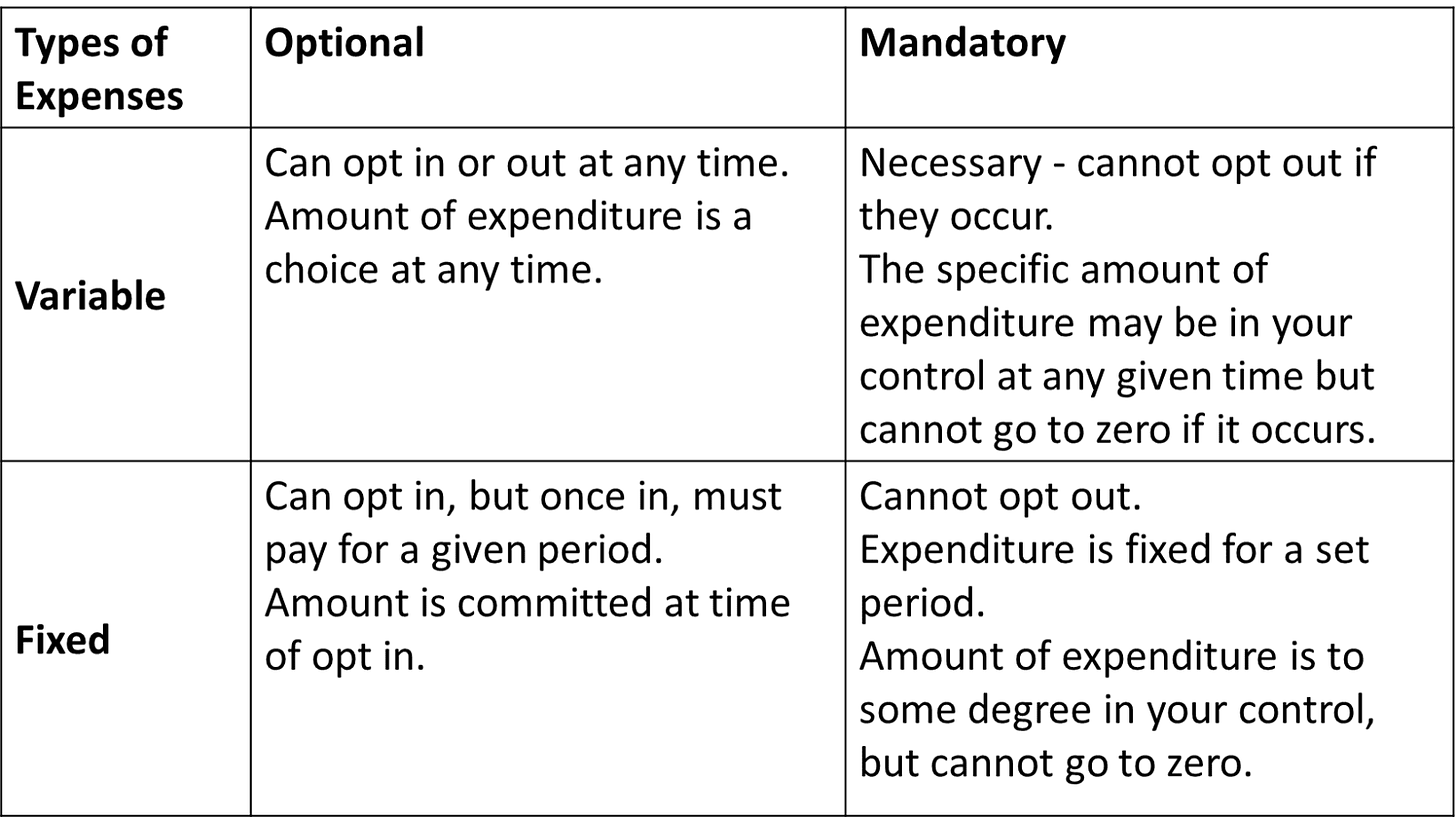

I use these two pairs of categories to make a 2x2 that combines them into four combined categories:

This is how I think about expenses. In the right column are all the things we don’t really have a choice about: food, shelter. In the left column are things we can choose to have or not - creature comforts and entertainment. The rows get at our commitment - things in the top row can be changed on the fly. Things in the bottom row constrain our choices in the future. Here are some examples:

Mandatory/fixed: First and foremost is shelter. When you sign a lease or buy a house, you probably incur your single largest regular expense. Once you commit, you have a long-term, recurring expense that you have to meet.The decision here is how big of a house do you want to commit to? And therefore, how big of a payment. But once the commitment is made, it tends to be difficult to get out of it. I add in here insurance because, although you may feel like it is optional, it really is not. Likewise with retirement savings: you are going to get old and at some point you will need retirement savings to survive. You can pretend you don’t need to pay into a retirement account, but the bill comes due regardless.

Mandatory/Variable: These are things you have to buy, but you can make choices at any given time on how much. You can spend a lot of clothing or a little. You can buy more or less. But you have to have some. You have to have furniture, but you don’t have to spend a lot on it, and you don’t have to have extravagant decor. You have to eat. You can eat at home or eat out; and you can choose to eat inexpensively at home or spend a lot. These are all things you have to do, but in any given period you can exercise choice. I add in here contingency savings because, like retirement, bad things are going to happen and you need resources to meet those challenges. You can pretend they won’t, but that won’t stop them from happening. It’s best to have a couple of months of salary set aside in savings for contingencies.

Optional/Fixed: Things that you choose to commit to that commit you to future expenditures. Buying a car is the example I already talked about. But think about all the various subscriptions you have committed to. Some are easier to cancel than others, but think about how many streaming services you subscribe to. Those are fixed expenditures. Some clubs have minimum commitments - many gyms require you sign up for a year’s membership. In this quadrant I put all the things that are fun and nice to have, but have a recurring cost. Like Mandatory/Fixed, this category reduces your future freedom.

Optional/Variable: Like Optional/Fixed, these are fun and nice to have things, but they don’t have a future tail that constrains your future freedom. One and done expenses. Eating out at a restaurant doesn’t commit me to a future stream of expenditures.

You should be picking up on a theme here: freedom of choice in the future. I think many people do not think through their choices using these categories and wind up committing too heavily to the expenses in the Fixed row and wind up feeling trapped by their previous choices. By maintaining freedom of choice in the future, you are giving your future self a choice in how s/he lives her/his life. You don’t want to put your future self in a financial prison as a result of your bad choices today. Bad financial decisions that lead to financial distress also lead to mental distress according to research (it’s pretty common sense, I feel obligated as an academic to cite the literature when I assert something).

Borrowing from Oberholzer-Gee’s Better, Simpler Strategy, I thought it would be useful to portray our financial resources as a stick. At any given time, we allocate our resources to the four categories I defined above (remember, savings is included in those categories, so all of our resources at any given time go to one of the four categories).

I’ve drawn the stick with equal portions going to each category, but of course that doesn’t have to be the case. Our choices affect how much of the stick each category takes up.

The bottom half of the stick are the fixed expenses - these constrain our future choices because once we commit, we are stuck with them. The upper half of the stick are choices that we can change in the future. So the more the bottom two categories take up of the stick the less flexibility we leave our future selves.

Above is a comparison of two distributions with the same financial resources (same length of stick). The distribution on the right represents someone who probably has bought a big house, and then bought a fancy car and maybe bought a bunch of nice things for her/his house on credit. Buying a big entertainment system should be an optional/variable purchase because you should buy it with cash. But when you buy something you don’t need for survival on credit, it moves from optional/variable to optional/fixed and constrains your future self. When your friends are going out or going on a vacation, and you can’t go because you have to make payments on your entertainment system, you feel the bite of your choice. As I talked about last week, this is what Thoreau meant when he said: "And when the farmer has got his house, he may not be the richer but the poorer for it, and it be the house that has got him."

Living a life with high fixed expenses can put one in real danger of financial ruin. If you lose your job, you still have to make all those payments you committed to. In short order you can wind up losing your car and your house. Being over-leveraged can put you at serious risk of not being able to meet your obligations.

The stick on the right represents someone who does not have much financial freedom and is constrained by her/his prior choices. This is a depressing way to live. This is why I say that the lieutenant-mobile is a bad choice. It swells the optional/fixed category unnecessarily and probably unwisely.

Rich people are happier because their resource stick is longer. They can have more of the fixed expenditures without reducing their financial freedom. In the above graphic, you can see that the top half of the wealthy (right) stick is almost as large as the whole of the modest (left) stick. So more wealth can give you more freedom. But also making careful choices can give you more freedom, even with less financial resources. You can make the Thoreau’ean choice:

You can see here that even with fewer overall financial resources, you can make choices with your fixed expenditures such that you can have more financial freedom.

My wife and I have always opted for the Thoreau approach. The distribution of our categories looks a lot like the stick on the right. You don’t join the Army and then become a professor at a state school in order to become rich (i.e., get a bigger financial resources stick). I’m not saying we’re poor - we do well for ourselves - but we’re modest. We made choices together for meaningful work and available leisure that resulted in a financial resources stick that is much smaller than what we might have gotten had we made other choices. But with the resources we had, we have always been very cautious about fixed expenses.

When I was in the Cav, we had only been married about two years. We met another married couple, the husband of which was a colleague of mine in Thunder Squadron. They were married so they didn’t have the lieutenant-mobile. Instead, they both drove BMWs. I remember after having gone out to dinner with this couple, my wife saying to me, “Why can they afford BMWs and we can’t?” My reply was something like, “They can’t afford BMW’s, either. They just don’t know it.” Had we bought BMWs instead of a sensible Civic (and a similarly sensible Saturn SL), our category distribution would have been consumed with optional/fixed expenses and left very little room for anything else. We both value freedom - today and in the future - more than having fancy things.

I’ve written about this before, but I remember the economist Tyler Cowen recommending the secret to financial success is “Cheap hobbies and good real estate.” By good real estate he meant buying something that you can afford in an area that you like that gives you easy access to the things you want to do. Just as important is the first part - cheap hobbies. We all have the same amount of time in the day. Finding meaningful leisure that is inexpensive is, in my opinion, one of the keys to a happy and satisfying life. As any of you who are long-time readers know, my hobbies are photography, art, kayaking, cooking, and now a return to jiu-jitsu. Photography can have a high, up-front cost. Getting some decent camera gear as you get serious can run a few thousand dollars, but once you have it, the marginal cost is roughly zero, especially since I do digital photography. What I mean by that is once I have paid the initial cost of the gear, taking a picture is basically free. So I can (and do) spend hours taking pictures and processing them. And this gives me great joy. Kayaking is the same. Once you have bought the boats, there is near zero maintenance cost. I can paddle all summer at the cost of the gas to get the boat to the water - which is also near zero because I have good real estate that is close to the water. Of that list, jiu-jitsu is probably the most costly, because it involves a optional/fixed membership payment. But relative to my income, the gym membership is very modest. These hobbies are good for me and they are cheap. At little expense, I get a great deal of satisfaction.

I have read and I have seen the toll financial mismanagement takes on individuals and families. If you are overleveraged and have too much of your expenses in the fixed portion of the stick, you can find yourself locked into a job you hate, living in a place you don’t like, with no time or resources to do the things you would like to be doing because your younger self made bad decisions and committed you to things you wish you weren’t stuck with. Making good financial decisions, which mostly means being very careful with the bottom half of the stick, can make your life much happier, even if your resources are modest. Finding good real estate and cheap hobbies is powerful advice.

My wife and I have consciously built a life that is not excessively materialistic, from back at the beginning of our marriage when I was in the Cav. That is our preference. We’re ok with a smaller resource base (stick) because we both came from modest backgrounds, and we feel pretty wealthy compared to what we grew up with. Because we have managed the bottom half of our stick carefully, we have a lot of financial freedom. We both like that a lot. By the way everyone in the Cav, including the lieutenants, joked about the lieutenant mobiles. Everyone has to find their way to the right mix of expenditures. Probably most of these guys found an equilibrium eventually, and probably it did not include driving a sports car, but maybe it did and does. I’m not saying you have to live an ascetic life, but having lots of financial resources comes at a cost. One should be thoughtful about such a choice. There is more to life than money can buy.