The Federal Budget: What are we fighting about?

Getting past political theater

I am a fiscal hawk. That means I really don’t like budget deficits. I don’t like them in my personal life and I don’t like them when the government runs them. When the government takes in more in taxes than it spends, that is called a budget surplus. When the government spends more than the amount of taxes it collects, that is called a budget deficit. When the government spends exactly the same amount of money as it collects in taxes, that is called a balanced budget. I will turn 55 next month. In my lifetime, the Federal Government has only had two years when it ran a surplus. Every other year it has run a deficit.

Taxes > Spending = Surplus

Taxes < Spending = Deficit

Taxes = Spending = Balanced Budget

As with most economic issues, deficits are not in and of themselves a bad thing. It all depends on why you are running a deficit. Think about it in the context of your own financial life. If you earned $100,000 and you spent $80,000, you would have a household surplus of $20,000. That sounds good. You can save $20,000 for a rainy day.

If you earned $100,000 and you spent $120,000, you would have a household deficit of $20,000. If you spent that extra $40,000 over and above the previous example on a fancy vacation, going out to eat a lot, buying yourself nice clothes, etc. that deficit would have been a bad idea. It’s a bad idea because you would have had to borrow $20,000 to fund your consumption. In the future you will have less money to spend because now you will not only have to pay back your loan, but you will have to pay interest on top of the amount you borrowed.

On the other hand, if you earned $100,000 and spent $500,000, you would have a household deficit of $400,000. That’s a big deficit. Is it bad? Well, what if you spent $80,000 on the costs of living, and bought a $420,000 house? Is that bad? I would argue probably not as long as you needed the house. In this case a deficit is the result of you making an investment in your future. You would have to pay back the principal on the loan and interest on the loan as well, but you would have a place to live for many years. By buying the house now, you could stabilize your housing costs and maybe even make sure they are lower in the future. TLW and I bought the LHH in 2015. Today our mortgage (loan payments, insurance, and taxes) is less than what our daughter pays in rent for a 2-bedroom apartment one town over. That was a very good investment.

Generally speaking, it’s a good rule not to borrow to finance consumption if you can avoid it. On the other hand, it is often a good idea to borrow to finance investment. Other examples of this include students borrowing money to go to college. Generally speaking, college is a good investment (lots of caveats here – maybe I’ll do another post on that).

Another reason it is ok to borrow is when there is an emergency, like you have a big medical bill and for whatever reason, insurance won’t cover it. This is consumption, but you don’t really have a choice.

As a fiscal hawk, I mind less if the government is borrowing to pay for investments. It bothers me that this is not in fact the case, nor has it been for most of my life. The government mostly borrows to finance consumption (a large part of which is funding healthcare).

The data that follows is extracted from GovInfo, the US Federal Government’s official website. You can find the data here:

https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/BUDGET-2025-TAB/context

I relied on Tables 1.1 and 8.1

When the government spends money it is called an outlay. I looked at the 2024 data, which is still being finalized, so at some point this may change slightly.

In 2024, Federal Government outlays were $6,940.9 Billion ($6.9 Trillion).

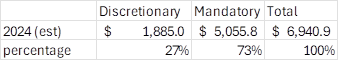

Outlays can be broken down into two broad categories: mandatory and discretionary spending. Discretionary spending means Congress decided year to year how much to spend. Mandatory spending means there is a law that says the Federal Government must spend a certain amount of money on a particular thing. Congress can change most of that spending by changing the law. The one exception is interest payments on the debt which we must pay or we default (bad things happen if we default – also another post of its own).

Just looking at this breakdown:

What goes into mandatory?

Social Security payments

Medicare

Medicaid

Other means tested entitlements (SNAP, WIC, TANF, etc)

Other non-means tested payments (transfers to states, etc.)

Interest payments on the Federal debt

That’s a lot of good stuff. I’m for most of it.

What goes into Discretionary?

Defense

Everything else

Defense is the Army, Navy, Air Force, etc. in case that’s not obvious. It’s big enough to warrant a call out. Everything else is what it sounds like – the State Department, Homeland Security, spending on roads, dams, student loans, NPR, etc. About half of the 27% goes to Defense and the other half funds everything else the government does other than Defense and the Mandatory programs.

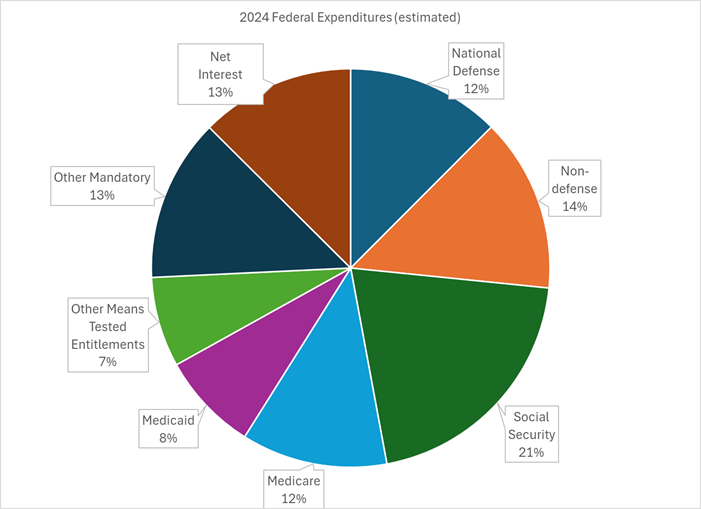

I think it is helpful to see the relative expenditures. Most people have no sense of what proportion of the Federal government’s outlays are for what purpose. Many people think we spend a great deal on foreign aid, but foreign aid is a tiny share of the “non-defense” discretionary budget.

How has this changed over my lifetime? Not that my lifetime is any special measure of time, but this is my newsletter and my lifetime is long enough now to capture a fair amount of change.

What stands out to me is the large shift away from military spending and towards social programs. In 1970 we spent 40% of the budget on the military, in 2025 we spend 40% of the budget on social security, Medicare, and Medicaid.

Is this a problem? Well, that depends on your values. But what is a problem is the fact that we are borrowing to fund these expenditures, and most of these expenditures are not investments. Where are the investments in our country’s future? Mostly in discretionary, non-defense, which is a puny 14%. Mandatory spending has been racing ahead of discretionary spending, and mandatory spending is largely consumption.

The real problem is the fact that we continue to borrow.

2024

Receipts $ 5,081.5

Outlays $ 6,940.9

(Deficit) $ (1,859.4)

We continue to borrow and we have nothing to show for it because most of the mandatory expenditures are consumed.

(see source here)

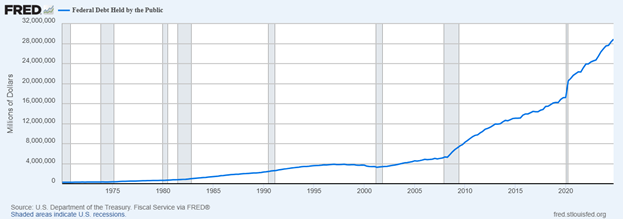

When we borrow year after year and never pay the debt down by running a surplus, we get a larger and larger debt that we leave to the next generation. You can see the debt really start to take off after the 2007-2010 financial crisis, and spike again during COVID. Another way to look at the debt is as a percent of GDP (the total income earned in the country):

I think this makes it much clearer that we have failed to be good stewards of the federal budget since 2007.

A responsible polity should be worried about leaving such a burden to our children. It’s really quite shameful to me. Our children will be hampered by this debt, and will be less likely to flourish. The responsible thing to do is bring down the deficit (and begin to control the debt). There are really only two ways to do that: spend less or tax more. If we appreciate the mandatory spending on social programs, we need to tax more to cover them. When politicians talk about cutting wasteful spending, they are really only able to address discretionary spending. Since the deficit is roughly equal to all discretionary spending, we would have to stop funding the military and all other government functions except our social programs. In other words, that’s just not possible. So when you see politicians not talking about raising taxes, and talking about cutting spending to get us to fiscal health, and they aren’t talking about cutting social programs like Social Security, Medicare, or Medicaid, then you know it is just theater. We need to either cut those programs to some degree or raise taxes. Those are hard choices, but that’s what leaders have to do.