Greetings from the University of New Hampshire! Can you believe mid-terms are already upon us? This semester seems to be rushing by at an increasing speed.

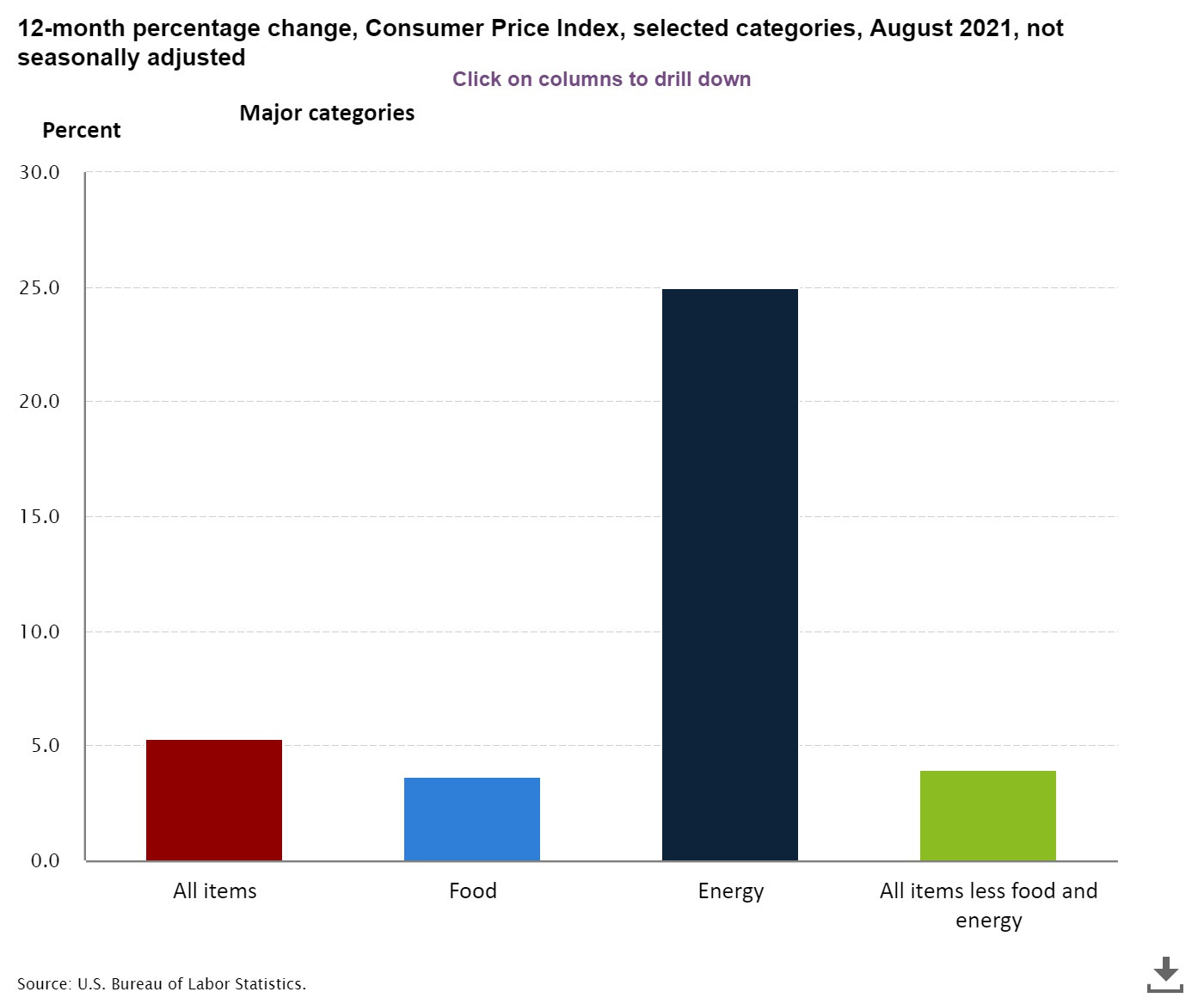

Speaking of increasing, the theme for this week is inflation. We have seen the first significant inflation in more than a decade. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics which tracks the official inflation metrics for the US, inflation was 5.3% from August of 2020 to August of 2021. The metric I am citing is the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which is the most commonly used metric for inflation. The CPI focuses on things consumers buy, like food, gas, clothes, cars, rent, etc. It doesn’t include changes in prices on things like jet engines or backhoes because consumers don’t buy them, and consumers are not directly affected by changes in the prices of those things. I have been thinking a lot about inflation and this past week it seemed a lot of the people I follow were also thinking about it, so I decided to take a break from talking about mentorship to talk about inflation.

We’ve had pretty low inflation for most of the last 30 years. The 70’s and early 80’s were brutal, with inflation peaking at about 15% in 1980 - the result of profligate government spending that began with the Johnson administrations combined spending on the War in Vietnam and his social spending agenda.

Source: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=HBr2

It took us through the 80’s to get inflation back under control and raising interest rates into the double digits to tame it. In the early 80’s you could get CDs at your bank that were paying 12%. (For reference, 5-year CDs are now paying about 1%). Millennials were babies when the last real inflation happened, and so they don’t remember anything but low inflation and low interest rates. And of course, Gen Z hadn’t been born yet.

The Read piece by Arnold Kling (below) brings up the concept of price stickiness. In some parts of the economy we expect prices to change all of the time. Gas is a good example, also fresh produce and meats. The BLS produces the CPI with energy and food in the CPI and with it pulled out.

Source: https://www.bls.gov/charts/consumer-price-index/consumer-price-index-by-category.htm#

Food and energy prices are typically not sticky - sellers can change the prices all the time and consumers don’t get upset. Other things we expect to stay stable and when they change, we get upset. Inflation messes with those expectations because everything starts getting expensive.

Inflation destroys financial wealth, disrupts economic planning, and makes it expensive to invest. If you are sitting on any cash, that cash now buys less than it did a year ago. That’s always happening, but it happened twice as fast this past year as it has in the past. Inflation disrupts economic planning because when companies make long term plans, they incorporate expected prices. For example, you are going to build a new factory and it will take you perhaps two years to build it, you will need supplies in the future. You make a plan incorporating the price you think the supplies will be, but if there is a bout of inflation, it can make your plans more expensive or not worth completing at all. We’re probably not there yet, but we could be. Finally, inflation has a direct effect on how much it costs to finance anything - whether that is buying a new home, borrowing for college, or starting a new business. The interest rates we think of when we go to buy, say a new car, are really based on two inputs - the real rate of return and inflation. The real rate of return breaks down into a number of other factors, but let’s just say for simplicity’s sake that it is the amount of interest a lender needs to justify lending to you. That’s the first half of the rate. Maybe it’s 3%. The lender then adds their guess about how much inflation is likely to be in the future on top of the real rate, because you are going to pay the lender back in future dollars which have been reduced in value by inflation. So if the lender thinks inflation is going to be 2.5%, the rate you are going to be offered is going to be 3% + 2.5% = 5.5%. If the lender changes her expectations about inflation going forward because she sees the government is spending $3.5T on “soft infrastructure” without a meaningful plan on how to pay for the new spending other than borrowing, she might increase her inflation expectations to 5.3%, so now you will be offered a loan at 3% + 5.3% = 8.3%.

Let’s compare the results of higher interest rates. Imagine you are planning to buy an entry-level house. The house costs $400,000. You have saved 20%, so you have $80,000 for the down payment to avoid mortgage insurance, and you will finance $320,000. Your payments with a 30 year fixed-rate mortgage at 5.5% would be $1,816 per month (this ignores taxes and home insurance). If rates rise to 8.3%, your mortgage would jump to $2,415 per month. That’s a 33% increase in monthly cost for the same house. Another way to think about the difference is at the lower rate, you could buy a new house and a new car for the same monthly payment as you would have to make for just the house at the higher interest rate. It’s a significant decrement to your quality of life. The Dalio interview (see Watch below) does a good job explaining how damaging inflation is.

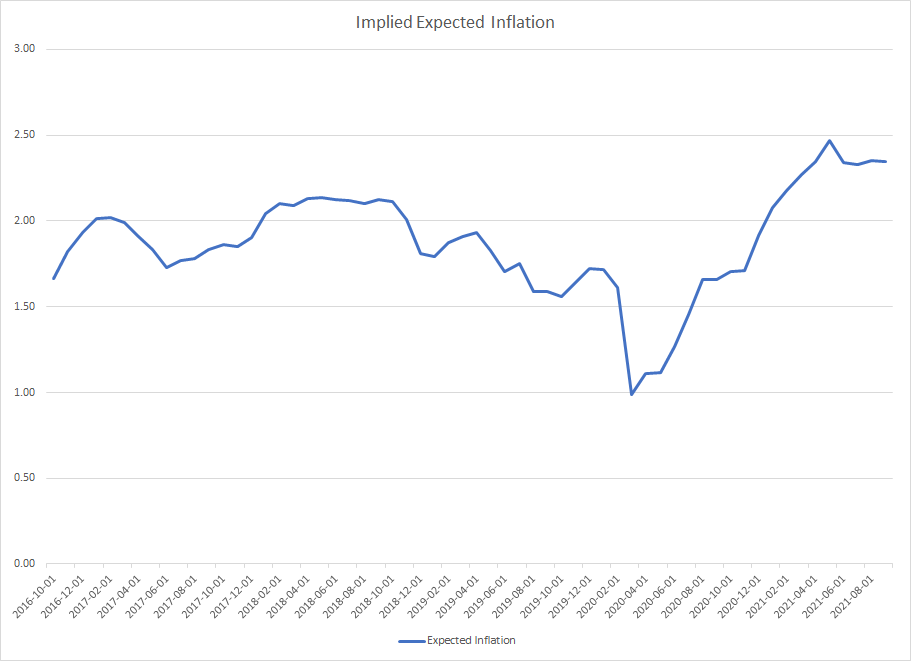

I’ve talked about the TIPS Spread before, but it’s relevant to any discussion about inflation, so I’m including an updated chart here. Investors buy and sell trillions of dollars of US Treasury Bonds every day around the world. It’s easy to find out what the current interest rate is on, say the 10 year bond, by looking at its market yield. This chart goes up through September 1st of 2021. On that day, the 10 yr bond had a yield of 1.37%. That 1.37% is composed of the real interest rate and inflation expectations (see the orange line below). The US Treasury also sells bonds called Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS). TIPS pay interest to the investors that hold them, just like regular bonds, but TIPS also make a second payment to the investors that hold them - and that second payment is equal to the CPI. So investors who buy regular bonds have to guess what future inflation is going to be and then they only buy bonds if the yield is at least the real rate plus what they think inflation will be. Investors who buy TIPS only have to worry about the real rate, because they know that the government will compensate them for inflation. TIPS bonds have lower yields because they only reflect the real rate of interest. This makes them interesting to compare to regular bonds. On the graph below, the blue line represents the yields from TIPS bonds. The gap between the blue and orange lines is referred to as the TIPS spread and it estimates how much investors think inflation is going to be (in this case, how much they think inflation will be over the next 10 years). On September 1st the TIPS yield is -0.97%, so the difference between the regular 10-year bond and the 10 year TIPS bond was 2.34%. This means that on September 1st investors were estimating that inflation would be 2.34% annually for the next 10 years.

Below I have calculated the TIPS spread over the last 5 years. If you compare the chart below to the chart of the CPI above, you can see investors were right most of the time - the CPI has hovered around 2%, which is what the TIPS spread from 2016 would have had you expect.

Data Source: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=HBik

Something unexpected has happened with the COVID pandemic, and we have had a variety of disruptions, leading to the sudden increase in inflation this past year. But if we look at the TIPS spread on the 10 year bonds, it would seem investors think inflation is temporary, and will go back down, and the 10-year average will be around 2.5%. If they didn’t think it was temporary, the spread would widen.

So, is the inflation we are seeing temporary? Or will prices continue to rise at a rapid rate? In the After Hours podcast (below), they discuss two things that I find indicate more inflation is coming. First, housing prices have spiked. I think that is likely due to constrained supply - people just aren’t selling their houses right now because they don’t want to move. I think that will change as the pandemic winds down. But a more secular trend in housing costs rising is the result of bad regulation - too much NIMBYism - too many restrictions on building. The good people of Durham (where UNH is) are very anti-growth. They get riled up when someone tries to pave a vacant lot that people have been parking in for years - and they use zoning to block simple things like that. In big cities like SF and NYC, zoning is even worse. There’s an excellent discussion of this in the first third of the podcast. The second thing they talk about that I have been hearing elsewhere is big companies, like Target and Amazon, are offering tuition assistance to their employees. This sounds generous, but they are doing it instead of offering raises. The tuition benefits come with strings attached - you have to stay for a certain amount of time after you take advantage of the benefit or you have to pay it back, so it’s more efficient for employers than simply offering a raise. It is also easy to end such programs if the labor market shortages don’t turn out to be long-lasting, so it’s a nice way to hedge your bets.

Going back to the graph, normally the blue line is a positive number because investors usually need a real return on their money when they lend it out. But as you can see, we have negative real interest rates, which is really unusual. This basically means investors are paying the government to take their money, which is really weird. The GoodFellows podcast (below) does a nice job discussing this, but they don’t have a real answer. John Cochrane, who is a well-respected macroeconomist, doesn’t get it, so I don’t feel bad not getting it, too. Their guest offers that the Federal Reserve is still buying Treasuries, but I have a bad feeling about this…

The GoodFellows agree that financial crises don’t emerge slowly. We usually build up to them, and then they explode, like the financial crisis of 2008. With the US Federal Debt over 100% of GDP, and Congress poised to add another 20% with the “soft infrastructure” bill, I think we are stacking barrels of gunpowder while smoking Marlboro’s. I think many of the programs in the soft infrastructure bill that I have heard about are nice, but frankly we can’t afford them because we are already in debt up to our eyeballs as a country. The nature of financial crises is we are all fine until we aren’t, and then it is too late.

Inflation is a terrible thing. It quietly robs people of the means to sustain themselves. You’re salary is worth 5% less than it was last year - so you are working today for less than you were last year. There is some discussion about what you can do to protect yourself - buy real assets like real estate and gold - but you can’t use your house to buy groceries - so you have to have some of your wealth in cash. The markets seem to think inflation will be controlled over the 10-year horizon, but our recent experience indicates we might be in for some bad times. And these negative real interest rates are very worrisome.

So, sorry for being a bit of a downer. I’ve referred to all of the links below in my discussion above, so the descriptions are short this week.

To the links!

Read

What: Arnold Kling, Are the laws of supply and demand broken? (short blog post)

https://www.arnoldkling.com/blog/are-the-laws-of-supply-and-demand-broken/

Why: According to Econ 101, there should never be shortages. But there are. So Kling talks about price stickiness and the incentives that real-world retailers face.

**

Watch

What: CNBC, Ray Dalio on How He’s Seeing the World Right Now (18 minutes, but just watch the first 7-8)

Why: Bridgewater Founder and Co-CIO Ray Dalio. He talks about three trends: debt/money supply, the political conflict over wealth, and China. I think he’s an apologist for authoritarian CCP rule, so I don’t give the last bit much credence. He certainly has economic interests that make him squint at Xi. His political commentary is not that interesting. But he does have some useful things to say about the markets, so I recommend the first 1/3 of the video.

**

Listen

What: Goodfellows, Economists Rule? (55 min)

https://goodfellows.podbean.com/e/economists-rule/

Why: Hoover senior fellows Niall Ferguson and John Cochrane are joined by economic historian Tyler Goodspeed, Hoover’s Kleinheinz Fellow and a former acting chair of the White House’s Council of Economic Advisers

**

What: After Hours, The Global Housing Crisis, Amazon’s Newest Employee Benefit, Women Outpacing Men in College Enrollments, Carbon Capture Goes Online, and More (40 minutes, but I was focused on the first 15 minutes for inflation theme)

Why: The discussion about NIMBYism in housing and the educational benefits are really interesting. The rest of the podcast is pretty good, too.

Thanks for reading and see you next week! If you come across any interesting stories, won't you send them my way? I'd love to hear what you think of these suggestions, and I'd love to get suggestions from you. Feel free to drop me a line at mark.bonica@unh.edu , or you can tweet to me at @mbonica .

If you’re looking for a searchable archive, you can see my draft folder here: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1jwGLdjsb1WKtgH_2C-_3VvrYCtqLplFO?usp=sharing

Finally, if you find these links interesting, won’t you tell a friend?

See you next week!

Mark

Mark J. Bonica, Ph.D., MBA, MS

Associate Professor

Department of Health Management and Policy

University of New Hampshire

(603) 862-0598

mark.bonica@unh.edu

Health Leader Forge Podcast: http://healthleaderforge.org

"Were there none discontented with what they have, the World would never reach anything better." - Florence Nightingale