I paddled the Oyster River early Saturday morning. The tide was going out, so I was able to take it easy and ride it, getting to the end of the river and the opening of Great Bay with less effort. It was a perfect day for a paddle - temperature at least initially in the high 60s, no wind, and an overcast sky that did not require sunglasses. The round trip is about six miles (three each away) and takes me about 90 minutes. I push fairly hard, but do pause to take pictures here and there, or to watch the heron, cormorants, seagulls, ducks, and the occasional eagle. I would say paddling (in my kayak or on my paddle board) is the closest thing I have to a spiritual practice these days.

This coming Wednesday I will be doing my first interview for the new Being in the World podcast, which will accompany and complement this newsletter. I’ll be talking to people whom I think have insights or practices that could inform us about living a better, more worthy life. My first guest will be Michele Dillon, PhD, the dean of UNH’s College of Liberal Arts (COLA). Dr. Dillon is a sociologist who studies religion, with a special emphasis on the Catholic Church. I am looking forward to talking with her about her work on the role of religion in society. She is the author of four books and many articles on the topic of religion. One of her books is coauthored with the psychologist Paul Wink, PhD, titled, In the Course of a Lifetime: Tracing Religious Belief, Practice, and Change. As the title implies, Dillon and Wink (“D&W”) looked at how people participate in religious practices throughout their life course. They did this primarily by using longitudinal data from a long-term qualitative study that interviewed people from the time they were young adults up into the late adulthood (in their 70’s). The limitations of the study include the fact that the study participants were born in the 1920’s, lived in California, and were of Christian faith (or atheist) by background.

Religion

One of the topics they looked at was the difference between religiousness and spiritual-seeking, and how those separate but not mutually exclusive practices changed and evolved over the life course of their participants, and what value either had to the participants. To operationalize religiousness, Dillon and Wink use a five point scale:

We rated the study participants' religiousness on a five-point rating scale assessing the extent to which institutionalized or church-centered religious beliefs and practices (e.g., church attendance and private prayer) were important in their everyday lives. This rating took into account whether and how frequently the interviewees attended church, whether and to what extent they believed in God and an afterlife, and how frequently they prayed and read the Bible; and the rating generally assessed the importance of religion in the participant's daily life. A score of five on our five-point religiousness scale indicated that church-centered or institutionalized religious beliefs and practices played a central role in the respondent's life denoted by belief in God, heaven, and prayer, and/or frequent (once a week or more) attendance at a traditional place of worship... A score of one indicated that institutionalized religion played no part in the life of the individual, as reflected in an explicitly stated lack of belief in God, an afterlife, or prayer, as well as in the absence of attendance at a place of worship. (p. 224)

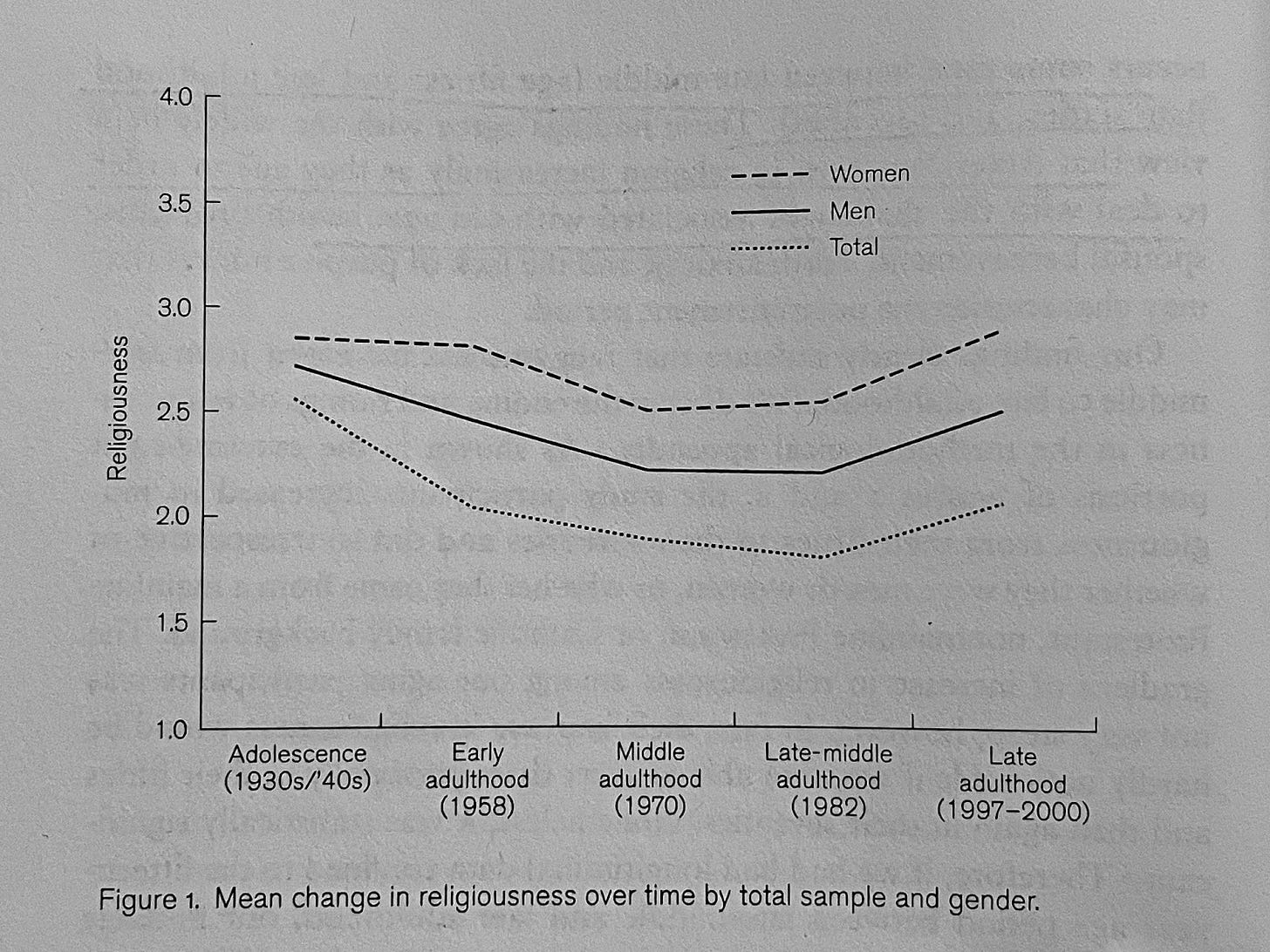

One of the interesting findings from the study was that religiousness tends to follow a U-shaped curve through the life course:

(clipped from p. 82)

These lines represent an average - some people are life-long atheists, some people start off religious and then drop off, some people start off with no religion and become religious. D&W note from their study that one tends to fall away from religion from early adulthood to midlife, and then start to return to one’s original level of religiousness in late adulthood. The uptick in religiousness in late adulthood had been well-known; their contribution was to show the earlier life connection, and that increased late-life religiousness was a return to the individual’s original levels.

This U-shape of religious engagement through the life course mirrors the U-shape of happiness I discussed in a previous newsletter. I thought it was interesting that these two life course changes map on to each other. I don’t have a specific explanation for this, but I thought it was interesting the D&W looked at two outcomes related to happiness that were impacted by religiousness: depression and life satisfaction.

D&W propose that “high levels of life satisfaction and low levels of depression are considered core indicators of successful aging” (p. 192). To examine the benefits of religiousness, D&W divided the participants into good health and poor health in late adulthood and then found that people who were religious experienced lower levels of depression in late life if they were religious, and substantially higher levels of life satisfaction. In other words, if you were relatively healthy in old age, religious practice didn’t make much difference to your happiness, but if you were dealing with serious illness (their examples were diabetes and cancer), religious practice was found to be protective of happiness.

Christian religious practice takes place in a social setting. Thus, people who are actively involved in Christian religious practice are less likely to be socially isolated. Social isolation is well known to have a negative effect on mental health. D&W claim that religious practice separate from social contact, has a positive effect on mental health. Having been raised Catholic, my comment would be that the Catholic Church provides rituals around all aspects of life that provide a sense of continuity and connection. While the Catholic Church’s rituals tend to be more highly formalized, my experiences with a variety of Protestant denominations has been that each of these communities has a set of rituals that provide structure to one’s life. I would venture to guess the protective effect of religious practice comes from the sense of meaning one gets from tradition.

Spirituality

According to D&W, about 1/5th of Americans “define themselves as spiritual but not religious” while “three quarters indicate they are both spiritual and religious” (p.121). I am surprised that the spiritual but not religious number is not larger. In academia, I hear this sort of statement all the time. I am also surprised that the spiritual and religious number is as high as it is (for reference, the book was published in 2007). D&W say that most of the religious and spiritual people use spiritual to describe their relationship with God through the church, but that for their study, they are defining spiritual seeking differently. D&W use the following definition and scale to rate spiritual seeking:

Our five-point rating of spiritual seeking assessed the extent to which non-institutionalized or non-church-centered religious beliefs and practices were important in the participants' lives. In order to be assigned a moderate or high score on spiritual seeking in our study, the individual had, among other core criteria, to express a strong interest in spiritual questions that, while focused on the transcendent or sacred nature of being, could include, but went beyond, the more conventional beliefs associated with institutionalized religion… Such beliefs and experiences alone, however, were not sufficient for the individual to receive a moderate or high score on our scale. Spiritual practices were also a critical element in our assessment of spiritual seeking. To attain a high score on spiritual seeking, the study participant had to report a systematic engagement in practices specifically aimed at incorporating a spiritual dimension in their everyday lives. In other words, simply being aware of spiritual feelings was not sufficient. Such awareness had to be accompanied by intentional spiritual practices such as meditation, for example. (p.225; emphasis mine)

As I understand it, spiritual seeking, according to D&W, is a “journey of self-discovery” (p.120). The population studied hit mid-life in the 1960s, a time during which there was a blossoming of alternative spiritual opportunities. It also coincided with the rise of “therapeutic culture” which we continue to see today. The goal of spiritual seeking is to come into closer contact with the divine, however defined, through pursuing a more authentic and integrated self. Although this is possible through established religion, the focus on authenticity may require rejecting traditional religion. Especially devout people can pursue spiritual seeking through their religion through prayer rituals and other approaches. Certainly Catholicism has a mystical tradition. I remember my grandmother, when she was in her 80’s, carried a Catholic prayer book in her house coat around the house that was well-worn. She prayed frequently using the book, as well as the Rosary. To me, these would be spiritual seeking tools within the Catholic tradition. D&W refer to spiritual seekers as using a variety of techniques to do their seeking. They mention meditation, drum circles, spending time in nature - but I think of tarot cards, crystals, etc - anything you could find in a New Age book shop. My parents were young adults in the 70’s, so I saw a lot of that stuff - not so much from them, but among their friends.

I thought D&W’s emphasis on action vs. statements of feeling was interesting. Economists generally dislike survey data where people are asked about their feelings and desires and instead prefer to observe what they actually do. You can say all sorts of things, but I know what you really value based on how you spend your time and your money. The emphasis on action, although the result of an interview, was interesting to me and sounded very economist-like.

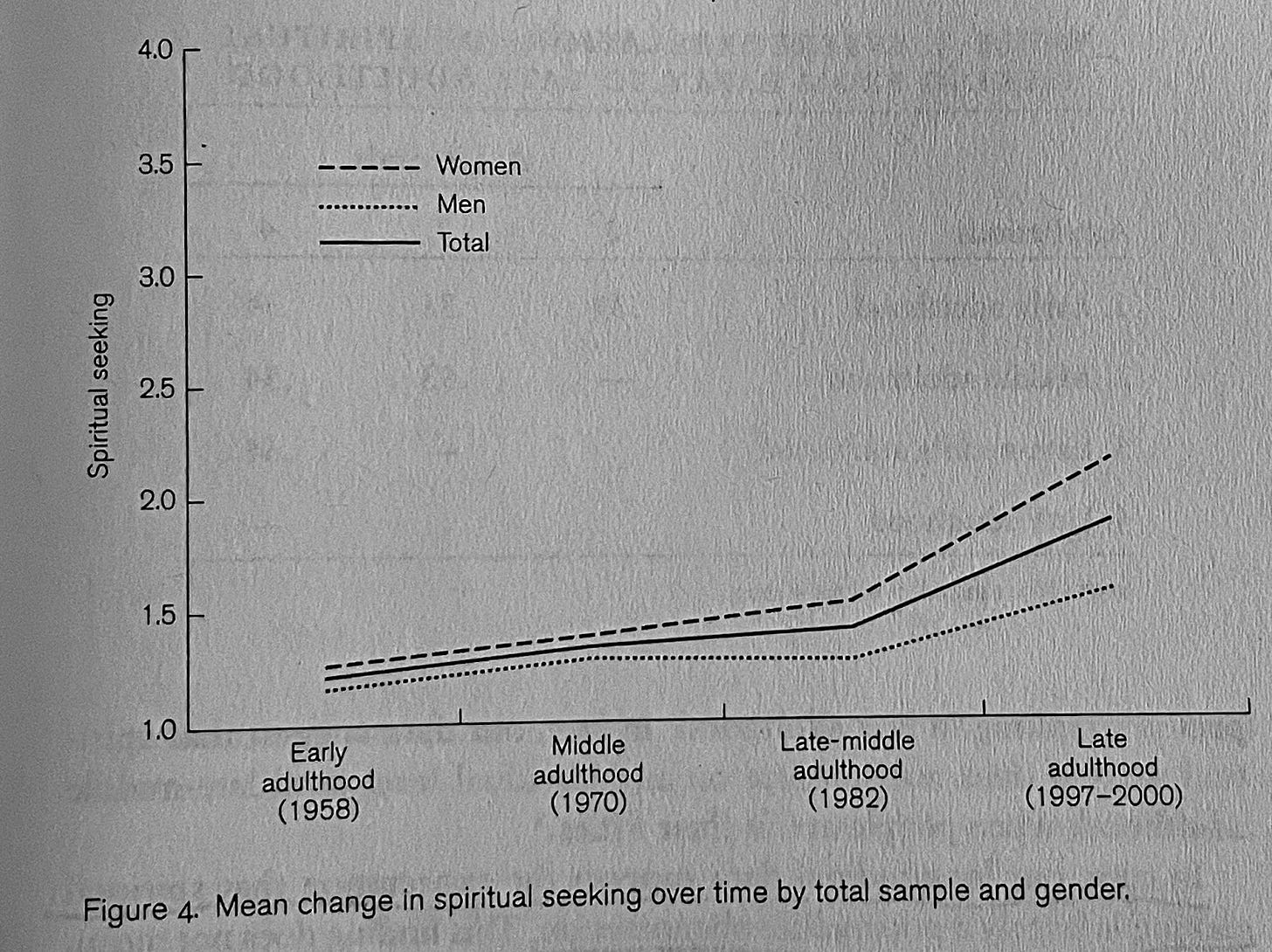

Spiritual seeking had a life course shape, too:

(p. 125)

I thought this was interesting because it mapped (to some degree) to the rise of crystalized intelligence I talked about previously, though crystalized intelligence rises earlier in the life course.

Unlike religiousness, spiritual seeking did not provide protection against depression or loss of life satisfaction, so high degrees of spiritual seeking did not help with successful aging in that sense. According to D&W,

Taking stock of one’s life may ultimately be conducive to a stronger and more integrated sense of self. But in the short term, it necessarily uncovers negative feelings that may not be conducive to either high life satisfaction or low levels of depression” (p. 193). D&W do assert that “spiritual seeking women… preserve their sense of control in the face of adversity despite not being buffered against depression and decline in life satisfaction” (p.194). Evidence from public health research, especially the Whitehall Studies, show that people who feel a sense of control over their lives tend to have healthier outcomes.

Conclusion

Religion in the United States has mostly been different from the rest of the world. The Constitution protects religious choice (and the choice not to be religious). In many parts of Europe, and frankly across most of the world, religious choice did not exist. Depending on where you lived, your religion was determined for you. The state had an official religion, and you had to pay a tithe to the church, regardless of your preference. Because of religious freedom, in America there have emerged a plethora of religions and religious practices. It is probably a major reason why more people identify as religious and engage in regular religious practice here than most other countries in the world.

Spiritual seeking probably predates formal religion, though that’s purely speculative on my part, and largely depends on definitions. As I was reading D&W, I pondered what my score would be on either of their scales. Probably low on both. I don’t regularly attend religious services. And, as much as I love my time on the water, it is only loosely about spiritual seeking in the sense D&W use. Exercise in nature is a powerful thing. I tend to sprint with the kayak until I am puffing, then slow down and appreciate my surroundings, then sprint again. The harder I work, the quieter my brain’s hamster wheel gets. There is a school of thought that being in nature itself is restorative to our well-being, but it doesn’t seem the psychological literature is conclusive on that yet. But after a hard paddle I do feel more at peace, more at one with the universe, than say a hard run on my treadmill in the basement.

D&W comment: “while religious engagement clearly enhances everyday existence, it is not always necessary to crafting a meaningful life” (p. 204). Spiritual seeking may also be adaptive for helping us retain a sense of control over our lives, even if it is not protective from depression or loss of life satisfaction. It seems practices of both may be useful.