I had the privilege of interviewing Kathy Kram, the founder of the academic study of mentorship in the workplace, on Friday afternoon. As part of my preparation, I read her co-authored book, Peer Coaching at Work. In the book she cites a concept called The Johari Window:

(click on the image to see the source article)

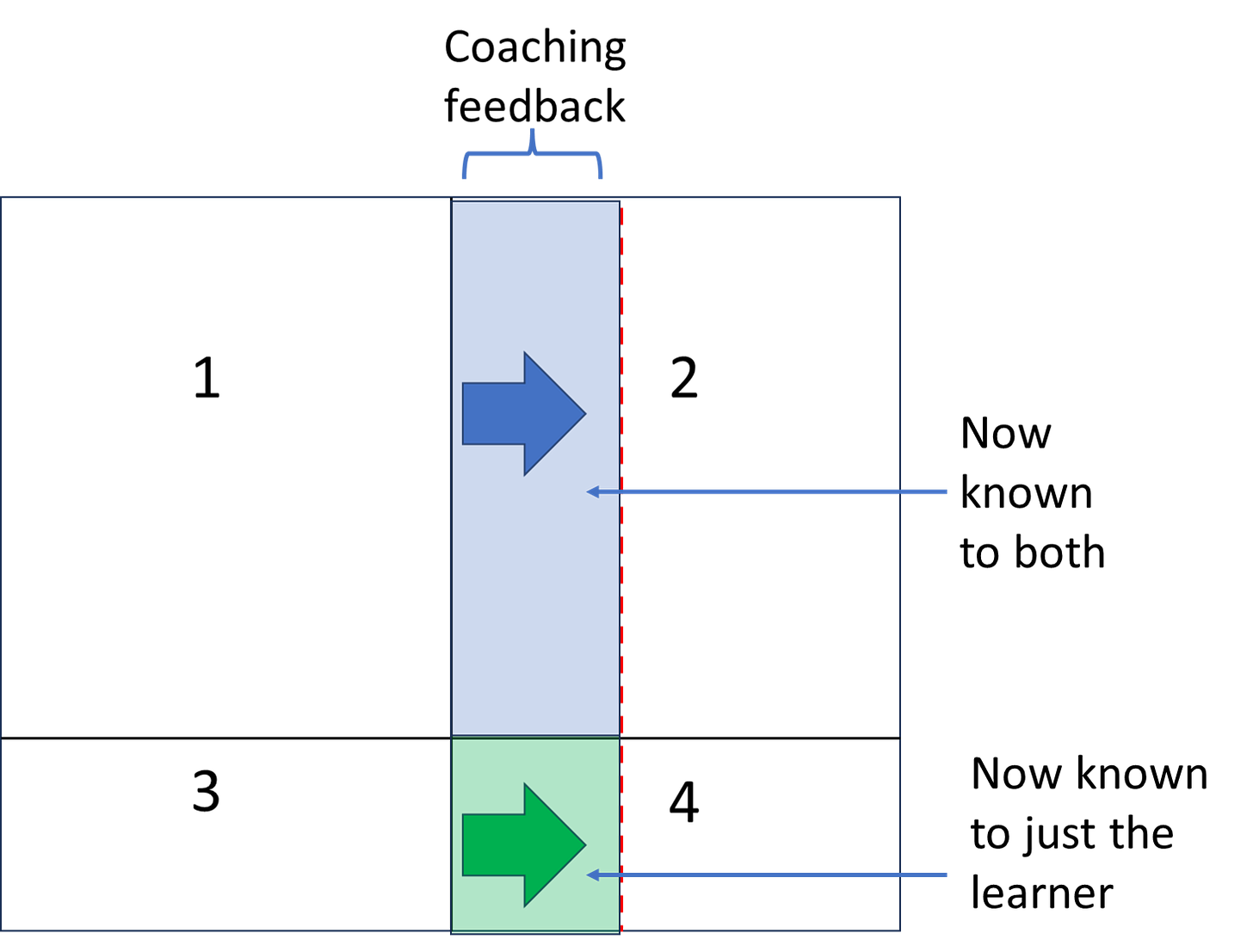

I hadn’t heard of the Johari Window before, or if I had, it had been long enough that I had forgotten about it. Regardless, I found the diagram useful for reflecting on the value of coaching. The Johari Window is created by deploying a 2x2 (I love 2x2s! - so useful!). When thinking about an area of yourself you want to improve, you can think of two axes: What you know about your ability in that area and what you do not know about your ability in that area; and what others know about your ability in that area, and what they do not know about your ability in that area. Combining those two axes creates the four boxes above.

Kram and Company use the Johari Window to talk about coaching in the workplace. That specific application is for people who are looking to improve their work performance. I think we can all easily think of areas where we would like to improve our performance. For example, I am always looking for ways to improve my teaching. I have some idea of my ability, as do my colleagues (Box 1). I’m aware of what is needed to be improved in this area. The goal is to make Box 1 as big as possible. The way to do that is to push into the unknowns.

Box 2 is where my colleagues, and my students for that matter, have insights into my teaching that I do not have because I cannot observe myself - I can only observe the responses from others. This knowledge that others have about me that I do not have (Box 2) is my blind spot. I am not aware of what I am doing wrong (or right) in this area. I need feedback from others to improve on these aspects. Do I have a verbal tic that distracts people? Is there something about my syllabi that could be improved? Etc. One tool I do have is the teaching evaluations that the students are supposed to be working on right now. I take those seriously. But another tool that I do not take advantage of often enough is inviting a colleague into my classroom to observe me and make suggestions. By seeking out help, I can push the boundary of Box 1 into Box 2. I think back on my professional career and I think of colleagues whom I was close enough with who would pull me aside if I was doing something and say, “Why are you doing that? You know you’re kind of being a jerk.” And that would snap my head around and I would try to fix whatever behavior I was engaged in. This also applies to positive performance. It’s helpful when someone you trust points out what you are doing well, too. Sometimes we’re so deep in the game that we don’t recognize what we’re doing well that is actually working. In fact, we might think the negative behaviors are the things getting results when in fact the results are in spite of the negative behaviors. I think this latter point applies to a lot of young leaders. My observation is they think exercising their hierarchical authority makes people respect them and want to follow them, when in fact it is usually more participative behaviors that make people want to follow a leader.

Box 3 is where I know something about my performance that others cannot observe. These might be my fears and anxieties. They may lead to performance issues or may be preventing further growth and improvement, but others can’t observe these things. I have to reveal them to someone else. Chances are, if I am keeping them secret, they are bothersome to me. They make me feel vulnerable. I need to have a relationship built on trust before I reveal them. When I reveal them, hopefully to someone who is prepared to help me, someone who is taking on a coaching role, I can push the boundary of Box 1 into Box 3.

The goal is to shrink Box 4 as much as possible and expand Box 1. As I contemplated the Johari Window, and in particular the idea of self-disclosure of Box 3 items, I was looking at how self-disclosure pushed the horizontal dividing line between 1 and 2 down into both 3 and 4. Even though my actions - self-disclosure - were meant to address the gap between 1 and 3, the result was 2 pushed down into 4.

The blue arrow represents my self-disclosure. I can act on the line between 1 and 3 by taking steps of self-disclosure. What the Johari Window shows us is that a by-product of my self-disclosure is that the person I have self-disclosed to can now understand my actions better, including actions that I am blind to myself - the area not known to me, but known to others - represented by Box 2. Now that my coach knows what I have been hiding, s/he will have further insight into the unknown/unknown Box 4, and can now share that with me (the green arrow).

Just like me, the coach can’t act directly on Box 4 - s/he can only act on the line between 1 and 2. But the virtuous effect is to shrink both 2 and 4. The green arrow represents the learner’s new insight into her/his hidden knowledge of her/himself. The little box the green arrow is in is new knowledge now known to the learner, but not known to the coach. While we want the new knowledge known to both, this is still an improvement, because now the new knowledge is known to someone (the learner) and can be shared, whereas before it was not known to anyone and remained a mystery.

The diagram at the top shows a shared discovery approach, but I don’t think that’s the right way to think about the process of exposing Box 4. I think the process is iterative, with the coach acting on the vertical line, and the learner acting on the horizontal line - and each responding to the new information created by those respective movements. I don’t think there is a diagonal approach - there are no bishops on this board.

Thinking about the Johari Window gives me more insight into how coaching can work, and the importance of iterating. I hope you found this as useful as I did. Next week I plan to talk more about iterating.