Economists are the OG appreciators of Diversity

A primer on comparative advantage and trade (part 1)

President Trump loves tariffs. There are few things the vast majority of economists agree on, but one of them is that tariffs are bad. Like, there are some economists who things tariffs are great, but there are also people who think the moon landing was fake. Economists look at “economists” who think tariffs are good like the rest of us look at people who think the moon landing was fake. Why? Well, because (almost) all economists agree that trade is (really, really) good. As in, the reason we aren’t digging in the dirt with sticks while dressed in animal skins good. I want to talk about why tariffs are bad, but in order to do that, I need to first show why trade is good. So today I will talk about why trade, intra-national or international, is good, and next time I will be able to build on that and show why tariffs are bad. Bear with me while I geek out.

Let’s start by imagining there are two countries: Big Country, which is a developed country with both a powerful agricultural sector that makes agricultural goods (Ag), and a powerful manufacturing sector that makes manufactured goods (M); and then there is Small Country, which is a developing country. Like most developing countries, Small Country has a focus on agriculture, and has a nascent manufacturing sector that is not very efficient.

If all of the people of Big Country organized their efforts and only worked on agriculture, they could produce 100 units of agricultural goods. If all of the people of Big Country organized their efforts and only worked on manufacturing, they could produce 100 units of manufactured goods. If all of the people of Small Country organized their efforts and only worked on agriculture, they could produce 50 units of agricultural goods, because Small Country is smaller than Big Country (that’s why they’re called Small Country). If all of the people of Small Country organized their efforts and only worked on manufacturing, because their manufacturing sector is more primitive, they could produce 10 units of manufactured goods. So to make 10 units of manufactured goods, Small Country would have to give up 50 units of agricultural goods.

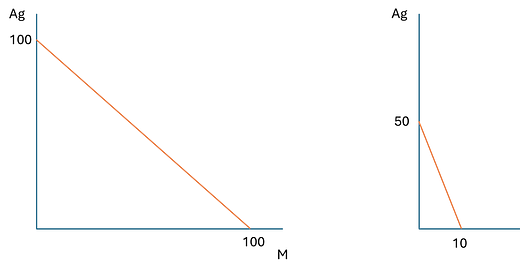

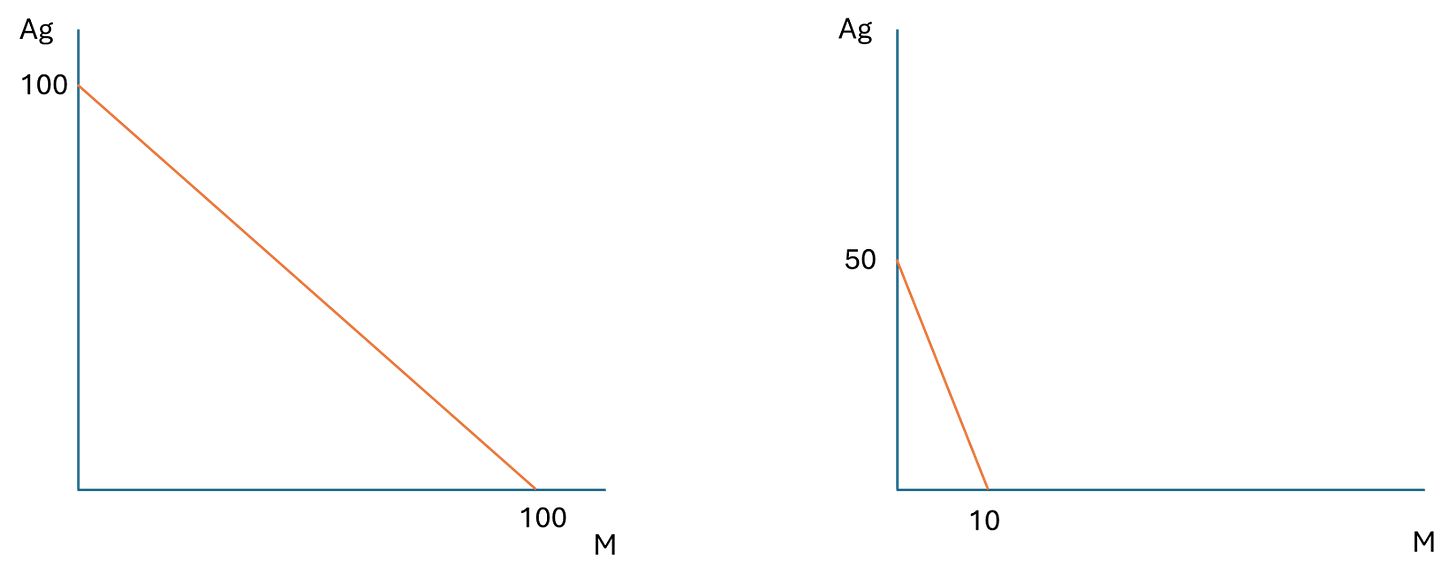

Graphically, the production possibilities of each country looks like this (Big Country on the left; Small Country on the right):

Big Country can produce any combination of Ag and M along the line. It can produce 0 M and 100 M, or 25 M and 75 Ag, or 50 Ag and 50 M, and so forth. Economists call the orange line Big Country’s production possibility frontier (PPF). By itself, Big Country can produce any combination of Ag and M so long as it is on the PPF, or inside the PPF. The examples I gave previously (e.g., 25 M, 75 Ag) are on the PPF.

Big Country could also produce say 20 M and 20 Ag, but that would be leaving possible production on the table and leave the people of Big Country less well-off, and for no reason, because Big Country can, by itself, produce along the PPF.

Big Country has a trade of of 1 unit of Ag for 1 Unit of M, as you can see from the line. If it started by producing 100 units of Ag, it could give up one unit of Ag and get one unit of M, so that it had 1 M and 99 Ag. Then it could give up another unit of Ag and have 2 M and 98 Ag, and so forth until it had 100 M and 0 Ag. What it cannot do by itself is produce to the right of the PPF. So for example, it cannot produce 50 M and 60 Ag. Whatever combination it produces, the total has to add up to 100.

Unlike Big Country, Small Country’s manufacturing sector is not as efficient as its agricultural sector. The trade off for Small Country is 5 units of agricultural goods for each unit of manufactured goods. They can make 0 M and 50 Ag, 2.5 M and 37.5 Ag, or 5 M and 25 Ag, and so forth.

It’s very costly for Small Country to make manufactured goods because they just aren’t very good at it. But they really need some Ag products and some M products, and so does Big Country. So let’s assume they both split their productive effort between each category.

So the starting point would be Big Country would make 50 M and 50 Ag, while Small Country would make 5 M and 25 Ag. These are states of autarky, or economic independence, where neither country relies on the other. This is a very popular idea among populists - we should be “independent” of foreigners. This works pretty well for Big Country since it’s so well-endowed with both agricultural and manufacturing capability. But Small Country could really benefit from getting some cheaper manufactured goods. Remember, it costs Small Country 5 units of agricultural goods to make one unit of manufactured goods, whereas it costs Big Country only one unit of agricultural goods to make one unit of manufactured goods. Looking at this arrangement, what does Small Country have to offer that Big Country would want? Why doesn’t Big Country just say “suck it” to Small Country? What does Small Country have to offer?

Big Country has an absolute advantage over Small Country in both Agricultural and Manufactured goods - it can make more of both (!) than Small Country can. It’s awesome to be Big Country. Don’t get me wrong. Small Country would happily be Big Country if it could, but it can’t. So let’s deal with the real world. So instead of looking at overall production, let’s look at relative production. To make one unit of manufactured goods, Small Country has to give up 5 units of agricultural product. That’s a lot! Whereas Big Country only has to give up one. BUT! And this is where it gets interesting - If we look at how much manufactured goods small country has to give up to make one unit of agricultural goods, that number is the inverse (i.e., flip the number over) - it’s ⅕. To make one unit of agricultural goods, Small Country has to give up 0.2 units of manufactured goods. That’s a bargain compared to Big Country’s 1 unit it has to give up. Small Country may have an absolute disadvantage in both, but it has a comparative advantage in agriculture relative to Big Country.

A comparative advantage is when you compare the relative costs of making goods in each country. Small Country has a comparative advantage in Ag, while Big Country has a comparative advantage in M.

Economists are the OG Diversity appreciators. It’s difference that drives comparative advantage, and it is difference that drives gains from trade. Wherever there is difference in productive capacity, there is an opportunity for gains from trade.

So how do these countries gain from trade?

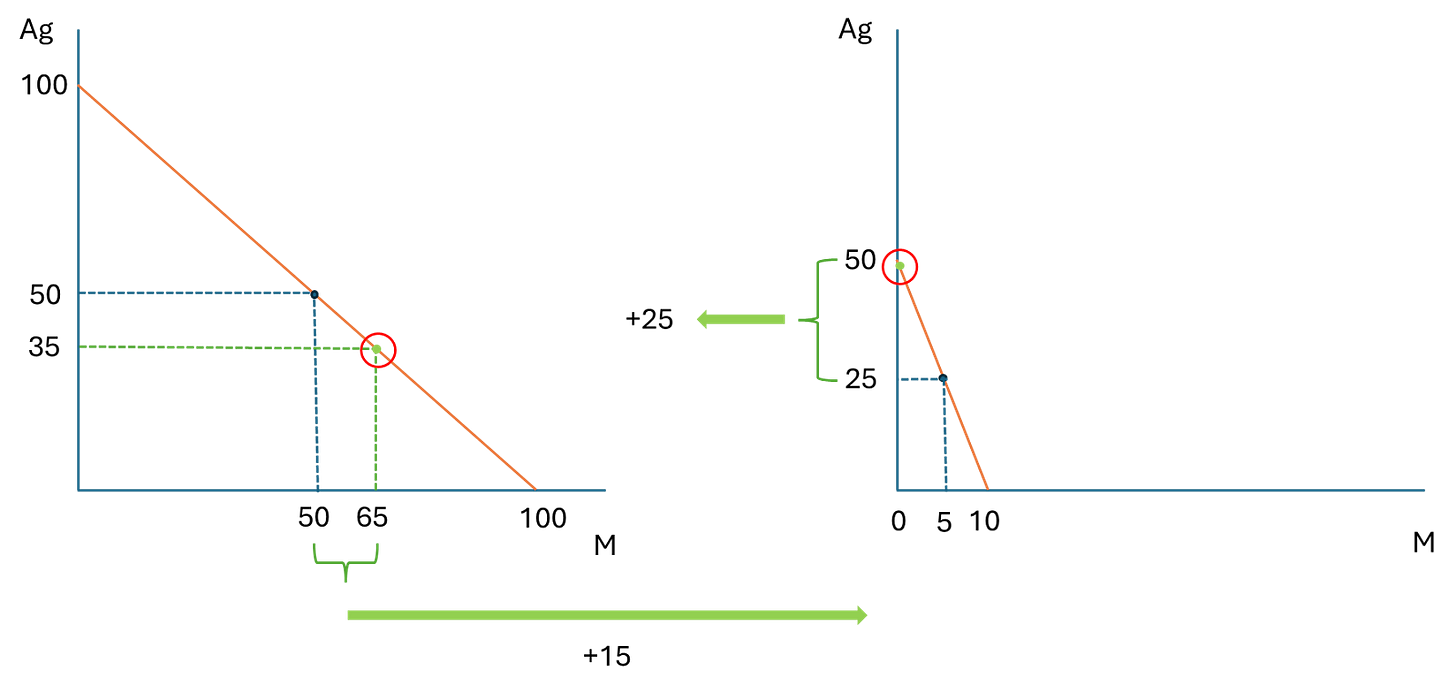

Let’s assume they start at 50, 50 and 5, 25 as I showed above. How can they trade and be better off? The answer is they can specialize. Big Country (right) can move some of its effort from Ag to Manufacturing, reducing Ag to 35 and increasing M to 65 (remember, it’s 1 for 1, so decreasing by Ag by 15 allows an increase of M by 15). Simultaneously, Small Country can abandon its manufacturing efforts and focus solely on Ag, reducing M by 5 and increasing Ag by 25 (remember for every 1 unit of M, it can make 5 units of Ag - its comparative advantage).

Now neither of these moves make sense by themselves. But if they each make these changes with the intention of trading, then it works wonders!

Big Country didn’t really want the extra 15 units of M, and Small Country didn’t really want the extra 25 units of Ag. But they made them to trade. So Big Country sends its 15 units of M to Small Country and Small Country sends its 25 units of Ag to Big Country. What’s the end result?

Big Country produced 65 units of M, but sent 15 of those units to Small Country, and kept 50. That left it with the 50 units of M it had under autarky (when it was working solo). Big Country only made 35 units of Ag itself, but then the ships from Small Country arrived with 25 more units of Ag, giving Big Country 60 units of Ag. After trading, Big Country has 50 M and 60 Ag, an amount of wealth it could not have produced alone.

Likewise, Small Country produced 50 units of Ag and no M, and shipped half of the Ag to Big Country, leaving it with 25, the same as under autarky. But then the ship from Big Country came in, crammed with 15 units of M, more than Small Country could have made on its own, even if it had given up all of its Ag, which it could not have done (since everyone would have starved). Small Country ends up with 15 M and 25 Ag.

Trade is a human super power. As Adam Smith points out in The Wealth of Nations:

Nobody ever saw a dog make a fair and deliberate exchange of one bone for another with another dog. Nobody ever saw one animal by its gestures and natural cries signify to another, this is mine, that yours; I am willing to give this for that.

And yet, human beings are naturally endowed with the ability to negotiate such deals constantly. As much as we can, we want to maintain free trade because it is in the interest of both sides. Human flourishing is contingent on free markets.

Next week I will discuss how tariffs throw sand in the gears of trade and make both sides worse off.